Evolving Needs of Critical Care Trainees during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study

J.K. Krishnan, J.K. Shin, M. Ali, M.L. Turetz, B.J. Hayward, L. Lief, M.M. Safford, K.I. Aronson

Summary

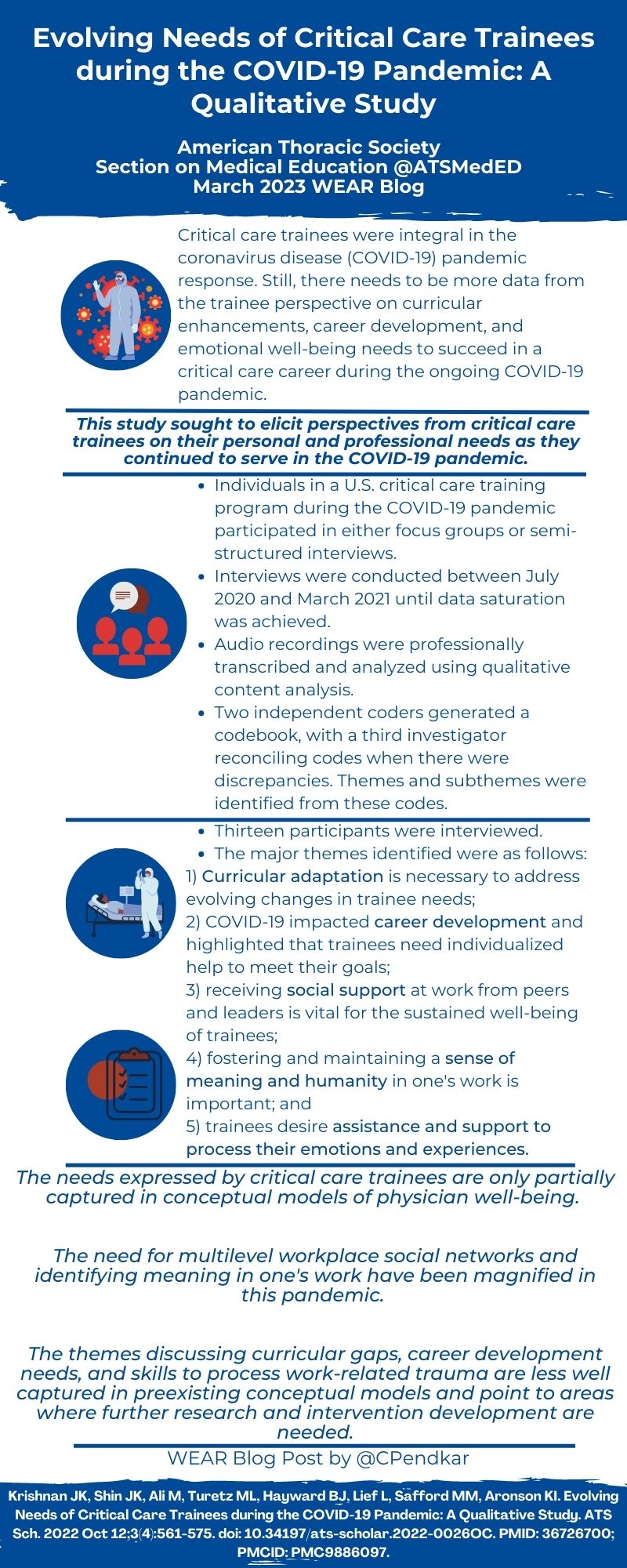

The COVID-19 pandemic produced innumerable changes to medical trainee rotation structure and education, some of which has been detailed in the literature. For trainees in critical care medicine, the dramatic increase in critically ill patients initially seemed in-line with their training goals, however likely resulted in challenges different than trainees from other specialties. Additionally, the pandemic’s emotional effects on critical care trainees had previously not been well explored. In this study, Dr. Krishnan and her colleagues utilized qualitative research methods, conducting individual interviews and focus groups with a total of 13 critical care trainees, to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic affected them personally and professionally. Through the analysis of critical care trainee narratives, five themes describing the various impacts and needs were elucidated – 1. timely curricular modifications are essential, 2. trainee career development requires a personalized approach, 3. relationships with co-workers preserve trainee well-being, 4. being able to draw meaning from one’s work is crucial, and 5. trainees seek guidance to process their work. By utilizing qualitative research methods to achieve their results, Dr. Krishnan and her colleagues were able to identify critical care trainee needs that were not previously realized in pre-existing conceptual models of physician well-being.

Interview

KM: Can you please briefly discuss your rationale for designing the study in this manner? What are the pros and cons of qualitative research?

JK: We organized this study during March 2020 during the pandemic when we saw how critical care trainees were central to the response at our institution. Critical care fellows were leading multi-disciplinary teams of physicians in “pop-up” ICUs throughout the hospital. While this led to a significant amount of leadership and autonomy, at the same time, there was an overwhelming amount of uncertainty and death. Because there was really no precedent for this, we decided to conduct a qualitative research study to better understand the impact of the pandemic on trainees.

Qualitative methods are valuable because they allow you to ask open ended questions to better understand someone’s experience, particularly when there might not be a significant body of literature on the topic. Through asking open-ended questions, you can capture nuances in responses or uncover unexpected ideas. Qualitative research can help explain quantitative findings with more context. Some of the cons are that qualitative research is labor intensive and time consuming, to coordinate and conduct multiple focus groups and immerse the research team in transcripts and coding. Qualitative methods acknowledge that there will be bias in interpretation and hence are often viewed as hypothesis generating methods.

KM: How did you decide upon your recruitment methods, and do you think this impacted the generalizability of your findings at all

JK: We were recruiting during the height of the pandemic in 2020 and used a variety of methods to recruit fellows across the country. This included emails to program directors that they could forward to trainees, posting on twitter and word-of-mouth. These recruitment methods can introduce selection bias in that the individuals who choose to participate in an interview-based study may be different than the general population of critical care trainees.

KM: Your findings were nicely summarized into 5 themes: curricular adaptation, career development, social support, sense of meaning/humanity, and support for processing emotions/experiences. What changes do you think your department/institution or other training institutions should make for critical care or any trainees, based on the findings of your study?

JK: Changes that can be made by training programs align nicely with the themes presented. For curricular adaptation, I think we are now in a phase where educational conferences are frequently on zoom or hybrid. While these facilitate more attendance, especially with multiple clinical sites, some of the social and networking aspects of conferences may be impacted. With regards to career development, trainees are graduating now, who were residents when the pandemic started. Based on the results of our study, the experience of working in the pandemic may have impacted their views of critical care and the sustainability of a critical care career. I think being proactive about reaching out to trainees who are close to graduation and reflecting on any career direction changes will be helpful. Finally, the theme relating to social support highlights that having strong work social networks and strong leadership skills among division/department leaders was extremely important for trainees to cope. I think being intentional about fostering social connectedness among fellows is important. In addition, identifying candidates with a track record of strong leadership skills and leadership training to fill leadership positions is vital.

KM: How do you think your findings should impact trainee deployment or support should we face another pandemic like COVID-19 again in the future?

JK: Potential things to think about with future trainee deployment and support are as follows:

- Feeling connected to other fellows was very helpful for trainees to cope. When thinking about deployment to other clinical sites, it is important that trainees are not isolated from colleagues.

- When fellows are deployed, they often must function with much greater autonomy and lead a team that is not a traditional critical care team. Building a scaffold of support- i.e., virtual meetings to discuss issues or always having an easily accessible backup attending to ask questions is important.

- Coping strategies vary significantly among different individuals. Not everyone benefits from group counseling. Some people need extra time off work to recover, while others prefer to be working to be around other individuals who are experiencing similar stressors. Some people have strong family support, while others will find family situations especially stressful in pandemic settings. Offering a variety of coping tools will be helpful due to the varying needs.

- As the surge of a future pandemic ends, it would be helpful to have a review to determine gaps in training and career development encountered by each trainee. Having an individualized plan to fill those gaps and support career development is needed.

KM: Which theme(s) or finding(s) do you think should be taken into consideration for trainees (critical care or more broadly) as we transition back to a “normal” life post-pandemic?

JK: With regards to career development, budgets at many academic centers are limited even more so after COVID, and newly graduated trainees may have to contend with less support for academic pursuits or available opportunities. Now, more than ever, efforts need to be placed to support the pipeline for women and individuals underrepresented in medicine. The fifth theme, support for processing emotions and experience is especially important. While exposure to traumatic situations was intensified in the pandemic, this continues to be an issue for critical care trainees. Day-to-day work in the ICU exposes you to stressful family dynamics, suffering and dying. However, there continues to not be consistent and systematic ways to support trainee mental health. The literature shows that trainees face considerable barriers to accessing mental health services despite desiring a referral. One such barrier is the need to disclose past mental health diagnoses on some work-related forms. Additionally, for some trainees experiencing distress, program directors may be the first point of contact. Training for program directors to navigate these issues could also be helpful.

Blog Post Author

Kathleen McAvoy, MD is currently a third-year fellow in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Yale University School of Medicine. She attended medical school at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and completed her residency training in Internal Medicine at Yale New Haven Hospital. During residency and fellowship, she developed an interest in medical education scholarship, and currently she is interested in promoting novel educational techniques by developing novel curricula in ambulatory pulmonary medicine and fatigue mitigation. Outside of work she loves to hike, kayak, and travel.

Article Author

Jamuna K. Krishnan, MD is an instructor and physician-scientist in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. After graduating from the University of Michigan Medical School with a dual MD/MBA, she moved to New York City for further training. She completed an internal medicine residency at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine. She continued at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine for fellowship training in Pulmonary and Critical Care. Dr. Krishnan is an early-stage investigator who is passionate about developing interventions targeted at overcoming healthcare disparities in chronic respiratory disease. Her current research program is focused on characterizing gaps in the optimal management of comorbid COPD and cardiovascular disease (CVD) among socially disadvantaged patients. Her research interests are informed by caring for patients in her COPD-focused clinic, where she has found that optimal comorbidity management in COPD is complex, requires significant care coordination, and influences outcomes. She is now using both quantitative and qualitative methods to design interventions to improve outcomes in socially disadvantaged populations with comorbid COPD and cardiovascular disease.

Twitter: @jkkrishnanMD