Article:

Development of Learning Curves for Bronchoscopy: Results of a Multicenter Study of Pulmonary Trainees

Voduc N, Adamson R, Kashgari A, Fenton M, Porhownick N, Wojnar M, Sharma K, Gillson AM, Chung C, McConnell M. Development of Learning Curves for Bronchoscopy: Results of a Multicenter Study of Pulmonary Trainees. Chest. 2020 Dec;158(6):2485-2492. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.046. Epub 2020 Jul 3. PMID: 32622822.

Summary:

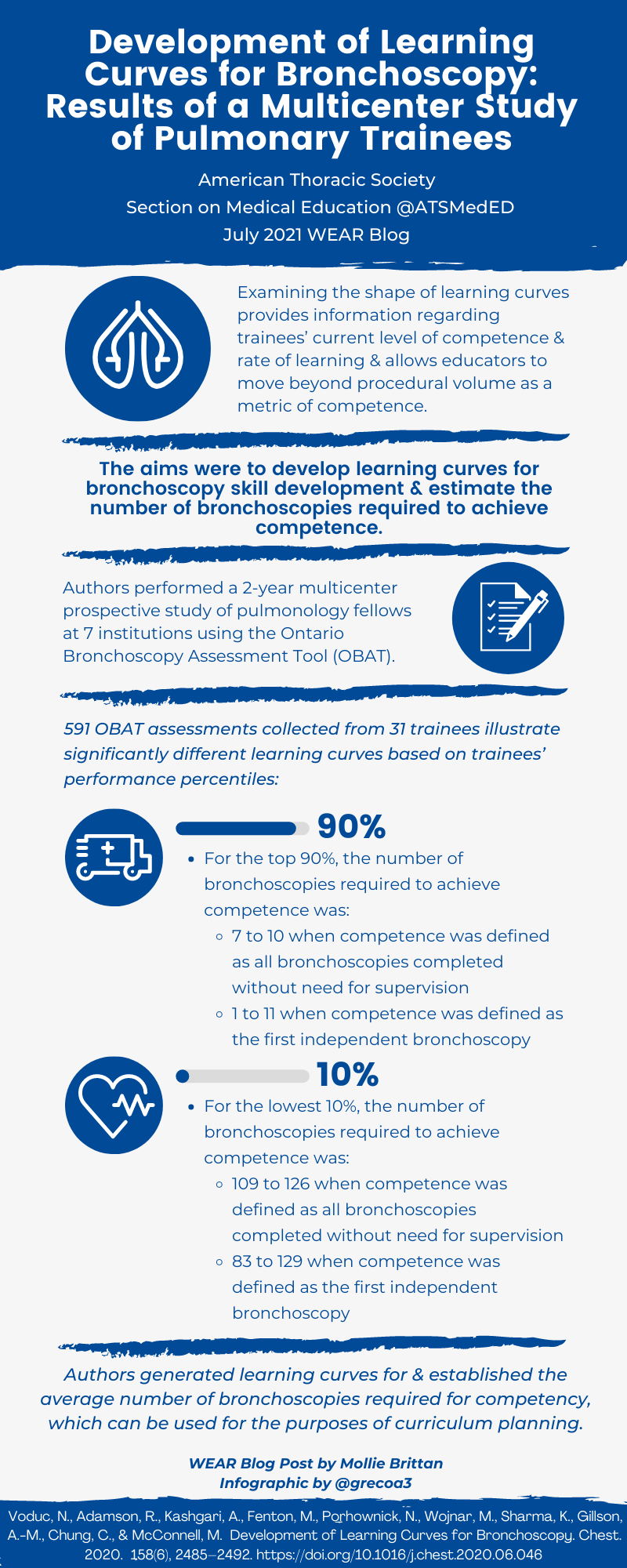

Mastering bronchoscopy is an essential skill for all Pulmonologists in training. In the past, professional societies and educators have recommended minimum numbers to gain competence. Recently, there has been a shift towards competence-based education. Competence-based education entails integrating specific metrics that aid educators in assessing trainees' skills with a specific procedure. This study sought to develop specific bronchoscopy learning curves across different percentile ranges of pulmonary trainees.

This study involved collecting data from 7 pulmonary training centers over a span of two years. The Ontario Bronchoscopy Assessment Tool was used (OBAT). The OBAT consists of a 12-item questionnaire completed by the educator. It is designed to assess bronchoscopy competence across the entirety of the procedure. Each item is graded on a 1-5 rating scale, with 5 being ''I did not need to be there'' and 1 being ''I had to take over''. The total score is graphed along with along with the number of procedures performed to create the learning curve.

After gathering relevant data from all participating sites, learning curves were constructed to obtain a performance-based metric of competence. The authors' analysis revealed that the number of procedures required to achieve competence varied significantly. For learners in the upper quartiles, there was an upward slope in competence in the first 25 procedures with a plateau in OBAT scores around 50 procedures. For those learners in the lower quartiles, the learning curve was much more gradual with OBAT scores plateauing closer to 100 bronchoscopies.

This study has some important educational implications as it gives educators a way to track learners' procedural competency. The results of this study show there is variation among learners in numbers of bronchoscopies needed to achieve competence. This allows educators to tailor bronchoscopy training to the individual learner and will allow for identification of struggling learners. By identifying struggling learners early, educators will be able to intervene and provide them with additional attention and learning opportunities.

Interview:

MKB: When and how did you first become interested in this topic?

NV: I was program director for Respirology (Pulmonology) between 2003 and 2020 so bronchoscopy teaching and resident evaluation was an important component of my job for many years. I first began to look specifically at the topic of bronchoscopy assessment around 2011. At that time, I was on a 6-month sabbatical, kindly hosted by Dr. Carla Lamb at Lahey Clinic in Boston. Dr. Lamb introduced me to the BSTAT and BSET developed by Dr. Henri Colt, which were the first validated bronchoscopy assessment tools. Around the same time, there was increasing talk among Canadian program directors about competency based medical education (CBME). I recognized that there was a need for an assessment tool that would be compatible with CBME. Furthermore, I felt that there was an opportunity to use this assessment tool to gain insight on bronchoscopy learning.

MKB: Do you feel there is an ideal number of bronchoscopies for a learner to perform to be competent? If so, what is it?

NV: A key message from the bronchoscopy learning curve study is that there was a wide range in the number of bronchoscopies required to gain competency. The majority of trainees would attain competence after performing the 100 bronchoscopies, a number which historically has been suggested as a minimum, but some trainees will require more training. Therefore, there is no "ideal" number.

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that bronchoscopy training is more than just volume of procedures. Training programs need to provide expert mentorship and a diverse clinical experience (e.g., bronchoscopy in critically ill patients, transthoracic biopsies, foreign body extraction, etc.).

MKB: How do you recommend that programs utilize the learning curves from your findings when developing bronchoscopy training? Have the programs involved in the study implemented changes in their bronchoscopy training or evaluation because of the study?

NV: The most useful aspect of learning curves is that they allow for early recognition of a trainee who may be struggling so that the program can provide additional support in a timely manner. For example, a trainee who is consistently scoring below the 25% percentile during their first 20 bronchoscopies could be provided with supplemental training (e.g., additional time with the bronchoscopy simulator) or their curriculum may be modified to allow for more exposure to procedures.

As the paper was just published last December, I think it is too early to tell whether it will have any impact on bronchoscopy training on other programs. Speaking for my own program, I can say that it was very useful to have learning curves against which I could compare my trainees' bronchoscopy performance over the past year. At my hospital, there was a substantial reduction in procedures for almost 6 months, at the start of the COVID pandemic, between March and September 2020. There was concern among my colleagues and trainees that this would substantially impact their ability to attain competency in bronchoscopy. However, OBAT scores from procedures performed after September indicated that all trainees were well on track in their bronchoscopy training and could be expected to attain competence in bronchoscopy well within their remaining training time. Consequently, significant modification to their curriculum was not required.

MKB: Do you feel this concept of learning curves can also apply to other procedures?

NV: Learning curves can definitely be applied to other procedures or "entrustable professional activities". However, there are two essential prerequisites: 1) is this procedure or activity important and complex enough that competence needs to be documented and 2) is there an assessment tool that is sufficiently reliable and sensitive enough to measure this learning.

Blog post author

Mollie K. Brittan, MD was born in North Platte, NE (small town in western Nebraska). She attended college, graduate school, and medical school at Creighton University in Omaha. She completed residency in Internal Medicine and a Chief Year at University of Nebraska Medical Center and is currently starting her second year of Pulmonary and Critical Care fellowship at University of Nebraska. In her spare time, she enjoys running, watching sports and spending time with friends.

Article author

Nha Voduc, MD graduated from McGill medical school and completed his Respirology training at Queen's University. He is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ottawa and served as the program director of the Respirology (pulmonary) training program between 2003-2020. His academic interests include cardiopulmonary exercise testing and medical education.