Article:

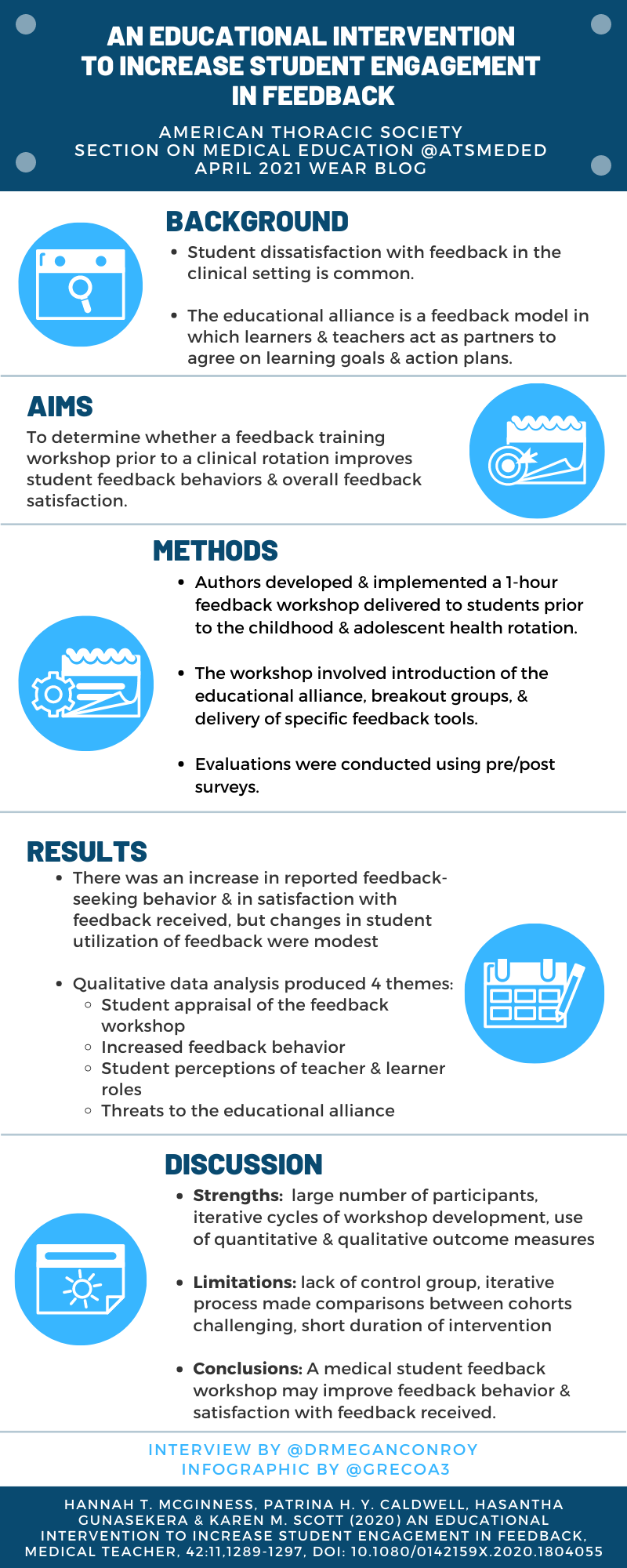

An Educational Intervention to Increase Student Engagement in Feedback

Hannah T. McGinness, Patrina H. Y. Caldwell, Hasantha Gunasekera & Karen M. Scott (2020) An educational intervention to increase student engagement in feedback, Medical Teacher, 42:11, 1289-1297, DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1804055

Summary:

Dr. McGinnis and colleagues conducted workshops on feedback for medical students entering pediatric clerkships, framing feedback as part of a learning cycle in which the learner must take agency and show self-advocacy in obtaining feedback. Their intervention of a one-off feedback workshop showed improved student satisfaction with feedback and students reported feeling that they had a more active role in the feedback process. There was no change in the utilization of feedback, and teacher factors and the clinical learning context modified the students’ agency in the feedback process.

Interview:

MC: A component of your intervention workshop included framing of feedback not as a one-way process, but rather as a cyclical process in which the student has agency to be an active participant. Many of our readers may not have approached feedback in this way, can you describe this conceptualization of feedback and the therapeutic alliance framework?

HMG: Historically, feedback was viewed as a one-off event where students were passive recipients of a judgement about their performance. Over the last decade or so, there has been a paradigm shift with the education community now coming to understand feedback as an ongoing cycle that informs learning, and the student is central to that process. Rather than simply receiving performance information when offered, students are encouraged to actively plan learning goals together with teachers, actively seek out opportunities for feedback related to those goals, jointly evaluate progress towards goals, and adjust learning strategies accordingly. Teachers guide, facilitate and input into this process but students are also key active participants.

The educational alliance is a very helpful framework for this newer understanding of feedback, developed by Telio et al [1] and based on the idea of the therapeutic alliance between doctor and patient. Cornerstones of an effective therapeutic alliance include a positive relationship between patient and doctor, jointly agreed upon treatment goals and a jointly designed pathway towards achieving those goals. So, in an educational alliance, feedback is most effective when it occurs in the context of a quality educational relationship and based on jointly determined learning goals and plans.

MC: Outside of this study, have you found the intervention of a feedback workshop to students to be a sustainable endeavor? How have you applied these findings in the learning environment with students? What are some ways that your workshop and findings might apply to faculty development?

HMG: We’ve continued to run the feedback workshop as a brief 30 min whole cohort session during orientation at the start of our paediatric clinical term. The brevity and incorporating it into orientation make it sustainable. We also encourage individual clinical preceptors to continue the conversation about feedback with students throughout their rotation. As a preceptor myself, In the clinical learning environment, I focus on helping students identify appropriate learning goals and opportunities, encourage them to ask for feedback and work with them to jointly evaluate their learning on a regular basis.

My top tips for faculty would be:

- Invest in the learning relationship – in our own and many other studies, students report engaging/disengaging from feedback based on whether they perceive their teacher to have an interest in them and their learning.

- As early as possible in the rotation, make time to sit down with your student and clarify learning goals. Allow students to lead this process, and work with them to identify learning strategies and opportunities.

- Encourage students to seek feedback but make sure you offer it as well. Make ‘feedback’ a joint discussion. Encourage the student to evaluate their own performance against their preset goals, then add your insights and encourage them to formulate a final view before jointly agreeing on the next steps for learning. Discuss with students how they will utilize the feedback to improve their professional practice.

- This process doesn’t necessarily have to take place over multiple long meetings – it can be condensed into a day or even a clinic.

MC: What suggestions do you have for a clinical preceptor in order to improve the reception and utilization of feedback by learners?

HMG: Invest in the quality of the educational relationship with your students. When students perceive they have a positive relationship with preceptors, they are more likely to seek feedback, be receptive to feedback, and utilize that feedback in future learning. Feedback that is aligned with a student’s learning goals is also more likely to be received and utilized for learning. An easy way to do this is to jointly agree on learning goals with students at the start of term (letting students take the lead), and ensure feedback relates back to these goals.

MC: Considering fostering life-long learning: what are best practices that educators can use to best seek and utilize feedback in our own careers?

HMG: As uncomfortable as it is (and sometimes increasingly so as we become more senior), we need to encourage a culture where we reflect on our practice, actively seek feedback from peers, and incorporate this into plans for improvement and growth as teachers. Our own continual improvement as educators and clinicians is so important, and our modelling of life-long reflection, learning and growth contributes to setting a positive learning culture at every level of the clinical team, students included.

References:

- Telio, S., R. Ajjawi, and G. Regehr, The "educational alliance" as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education.Acad Med, 2015. 90(5): p. 609-14.

Blog Post Author

Megan Conroy, MD is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. She is a student in a Masters of Educational Studies program with clinical interests in difficult to treat and severe asthma, and in medical education. She is a member of the steering committee for American College of Chest Physicians Airways Disorders NetWork.

Twitter: @DrMeganConroy

Article Author

Hannah McGinness, MBBS is a Paediatrician working in rehabilitation at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and a Clinical Lecturer with the Sydney Medical School (Discipline of Child and Adolescent Health).