A Tool to Assess Competence in Critical Care Ultrasound Based on Entrustable Professional Activities

H. P. Israel, M. Slade, K. Gielissen, R. B. Liu, M. A. Pisani and A. Chichra. A Tool to Assess Competence in Critical Care Ultrasound Based on Entrustable Professional Activities. ATS Scholar. ePub Jan 2023. DOI: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2022-0063OC.

Summary

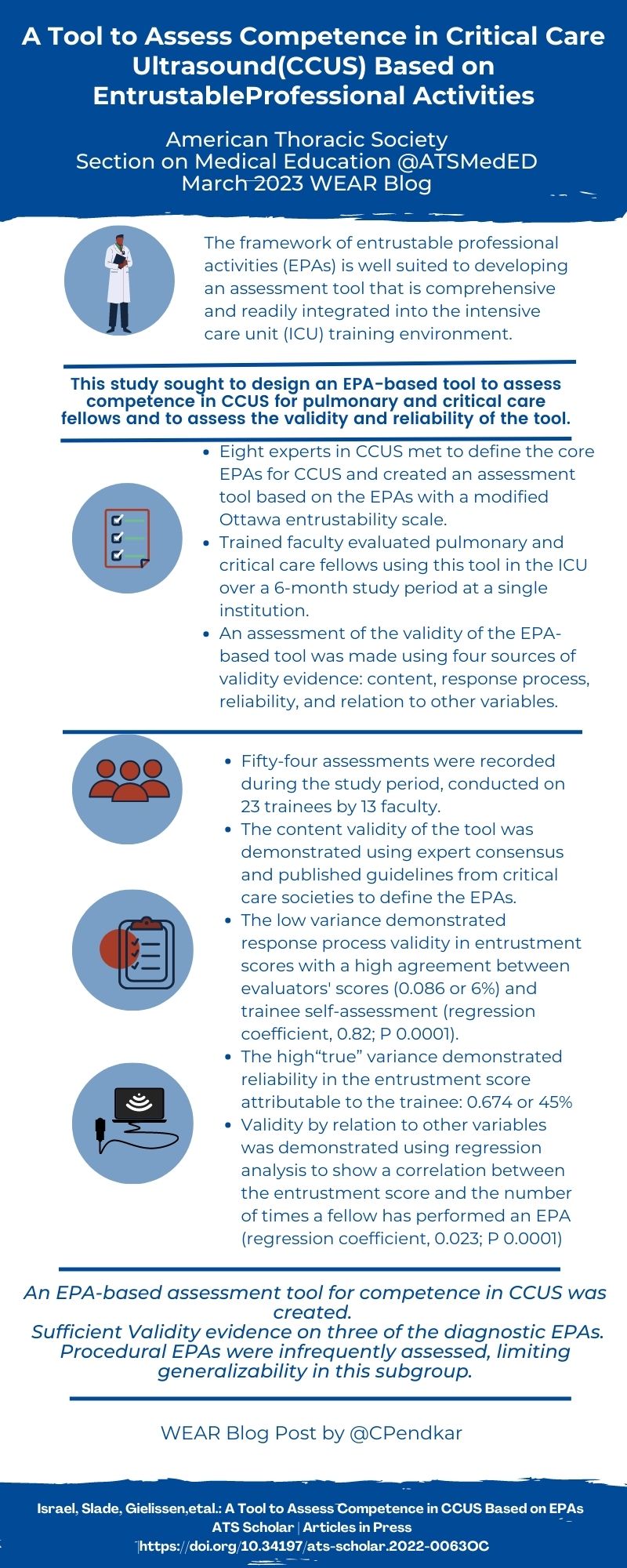

Competent performance of critical care ultrasound (CCUS) has become a core component of training in pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM). However, current literature on assessment methods for competency to perform CCUS suggests there is dearth of comprehensive, practical and standardized tools for medical educators to work with.

Israel and colleagues designed a tool to assess competency in CCUS for PCCM fellows, based on the concept of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs), definable clinical tasks that can be entrusted to a trainee once they have demonstrated the competence to perform the task unsupervised. First soliciting consensus-based feedback from a nationwide group of experts, the investigators defined seven diagnostic EPAs (e.g. “Evaluate a patient with hypotension or shock”) and four procedural EPAs (e.g. “Perform ultrasound-guided central line placement”). The assessment tool they created included a checklist of critical actions for each EPA encompassing four subdomains of indication, acquisition, interpretation, and medical decision-making (a framework known as I-AIM). The tool also included a modified, 5-point Ottawa entrustability scale, to be completed by faculty assessors who received training on use of the tool.

Over a six month period, the investigators recorded 54 assessments of 23 trainees, mostly pulmonary-critical care fellows, by 13 attending intensivists. Adjusted linear regression analysis demonstrated that the only independent variable significantly associated with entrustment score was the number of times a trainee had performed the EPA, including after a sensitivity analysis was performed (regression coefficient, 0.32; R2, 0.40; P < 0.0001). To estimate the magnitude of effect of different facets on entrustment score, they performed a generalizability theory analysis. The variance in entrustability scores attributable to the trainee (0.674, 45% of total variation) was much higher than other facets, for example the evaluator who completed the assessment (0.086, 6% of total variation)

This CCUS assessment tool and the study of its content and response process validity by Dr. Israel et al. is a major contribution to the literature on the use of EPAs by PCCM training programs. The EPA framework is well-suited for CCUS competency assessment and as Dr. Israel and her colleagues note, instruments like theirs could be an important part of developing more formalized pathways for certification of CCUS competency by PCCM fellowship programs.

Interview

MA:In this study, you developed seven diagnostic and four procedural entrustable professional activities (EPAs) related to CCUS. Can you describe how EPAs differ from other frameworks for assessing trainee performance, for example the ACGME's Milestone competencies?

HI: Thank you for that question. EPAs are a unique framework for assessing trainee competence. Medical education has historically relied on knowledge-based, written testing and performance of a large volume of clinical work to ensure competence of trainees on graduation. This common-sense education model was shaken by the introduction of “best evidence medical education” in 1999 which advocated for evidence-based medical education. As it has become clear that knowledge-based testing and extensive clinical work are insufficient and clumsy tools for assessing and shaping doctors, there has been a push towards competency-based education. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has implemented what is termed the Next Accreditation System in which six competency domains (medical knowledge, patient care, systems-based practice, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, and professionalism) provide the framework for curriculum and learning objective development in residency and fellowship training. While this framework certainly improves upon the common-sense model of medical education, some medical educators feel that these competency domains are nebulous and difficult to use in quantifying observable progress of trainees. In response to these criticisms, a more intuitive approach was proposed by Olle Ten Cate in which learners are assessed in the context of Entrustable Professional Activities, or EPAs.

An EPA is a complete task performed in the context of authentic clinical work that can be entrusted to a trainee once he or she has demonstrated the competence to perform this task unsupervised. An EPA differs from a competency in that a competency represents the overall skill of a learner and hence can be vague, whereas an EPA represents an observable unit of clinical work and is more concrete. Assessment of EPAs is framed as permission to perform the task with varying levels of supervision or help. Learners are eventually “entrusted” to perform the activity without direct supervision. Medical educators make entrustment decisions every day while working with trainees, and these ad hoc entrustment decisions are based on many factors including trainee ability, trainee trustworthiness (such a conscientiousness and knowing when to ask for help), supervisor familiarity with the trainee, supervisor style (lenient vs strict), clinical context and stakes, and the nature of the EPA (simple vs complex, common vs rare etc.). In an attempt to operationalize this decision-making process, various scales have been created to measure entrustment. These “entrustability scales” are ordinal rating scales that define the level of supervision a trainee requires to complete an EPA.

MA: Please tell us more about the I-AIM framework that defines four sub-competencies of POCUS.

HI: The acronym I-AIM was proposed by Bahner in 2012 to define four sub-competencies of POCUS: indication, acquisition, interpretation, and medical decision making. This framework has been widely adopted for use in curriculum design and assessment, and is conceived as a hierarchy of skills which range from basic learning to high-level integration. For a trainee to be fully competent in the use of POCUS for patient care, he or she needs to have mastery of each sub-competency. A trainee who can obtain a high-quality apical 4-chamber view of the heart but cannot differentiate the left ventricle from the right ventricle and cannot articulate the limitations of POCUS for cardiac assessment cannot safely use POCUS to take care of patients. An ideal assessment tool will encompass all I-AIM domains to capture overall trainee competence in the use of POCUS.

MA: You worked with a group of eight intensivists throughout North America to develop your EPAs. What is the nominal group technique for reaching consensus among a small group of experts?

HI: A nominal group technique (NGT) is a systematic method for reaching consensus among small groups of experts. The NGT is designed to promote group participation in the decision-making process. Prior to the meeting, the NGT facilitator prepares the single question that clarifies the objective of the meeting, in this case, “What are the core EPAs for POCUS competence for pulmonary and critical care fellows?” The steps employed in the nominal group process for reaching consensus are generally: individual silent idea generation, round-robin recording of ideas, serial discussion of ideas, preliminary voting, discussion of preliminary voting, and final voting. Voting can be done with methods based on rating or ranking. The ideal group size for a nominal group is five to nine experts. This size strikes a good balance of having enough different critical perspectives but not creating an unwieldy number of ideas to discuss. An NGT is useful when a decision-making process is complex and requires the pooling together of multiple sources of expertise. It is efficient because a group consensus can be reached by the end of a single intensive meeting.

MA: You describe the application of generalizability theory to analyze the magnitude of effect for several sources of variance, called facets, in your CCUS entrustment scores. You found that the "trainee" facet accounted for 45% of the total variability in your analysis; in contrast, the "evaluator" facet accounted for only 6% of the variability. How does this strengthen the validity of your assessment tool?

HI: Thank you for this question. I imagine many readers are unfamiliar with generalizability theory, and it can be a powerful tool for statistical analysis. The concept of reliability is classically conceived as consistency or reproducibility of assessment scores across multiple assessors (inter-rater reliability) or at different points in time (test-retest reliability). This framework cannot be used for assessments that occur in the workplace and hence will not be repeated. Generalizability theory provides an approach to estimate the effects of multiple factors (called facets) that contribute to variability in assessment scores. In our model, the facets considered are the trainee, the evaluator, the EPA, and the multiple interactions between trainee, evaluator, and EPA. In this dataset, the trainee is the object of measurement, or the element that the tool is designed to assess, hence the larger percentage of variance accounted for by the trainee, the greater reliability of the assessment tool. The percent of total variance attributable to the trainee in this analysis is 45%, which far outweighs any of the other facets. The 6% of variance attributed to the evaluator shows that attendings differed somewhat in their assessment criteria, but these differences were far less than the differences in the performances of the trainees. The 47% of variance that remains unexplained represents the summed effect of facets that were not considered in the calculations as well as error. These could be facets such as clinical location of the assessment, complexity of the case, time allotted for performance of the assessment, quality of the ultrasound available, and many others. The amount of unexplained variance can be understood by considering the nature of workplace-based assessments; EPAs performed during genuine clinical work cannot be standardized. This amount of unexplained variance is not dissimilar from other tools studied in medical education literature and could be reduced in future analysis by including more facets such as case complexity in the analysis.

MA: The ACGME core program requirements for PCCM training programs touch only briefly on the use of POCUS, as you and your colleagues note in your article. Is this a potential barrier to more widespread, formal assessment of competency to perform CCUS by PCCM fellowship programs?

HI: It’s true that the ACGME core program requirements mention POCUS briefly and describe the required competencies of trainees in only broad strokes. This could certainly be a barrier to more widespread implementation of formal competence assessments. However, I’m hopeful that competence assessments based on EPAs will advance despite this. One reason I’m hopeful this will be the case is that trainees are hungry for POCUS education. The strength of POCUS education in PCCM fellowships has been recently recognized as particularly important for recruitment. I think training programs will continue to improve their POCUS training since this is something that residents are prioritizing as they choose where to train. Another reason I believe EPA-based assessments will continue to be implemented is that they can be used for all training competencies, not just POCUS. EPAs are gaining popularity at all levels of medical education including UME and GME, and are arguably the best way for a training program to assess all desired competencies. As more work is published demonstrating the strengths of EPAs as assessment tools across multiple disciplines and contexts, I believe most training programs will implement EPAs as their primary method of trainee competence assessments.

Blog Post Author

Dr. Mark H. Adelman is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and a critical care attending physician at NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn, where he is also a site director and an assistant program director for the NYU pulmonary and critical care medicine fellowship program. His research interests include procedure competency assessment methods among GME training programs, specifically the use of medical simulation in curriculum development and ACGME milestone assessment, with a focus on objective, structured clinical exams.

Twitter: @PCCMinBKLYN

Article Author

Dr Hayley Puffer Israel is an Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care at the University of New Mexico. She completed her Internal Medicine intern year at Columbia, her Internal Medicine residency at Yale, and her Pulmonary and Critical Care fellowship at Yale. During her fellowship she also completed a master’s degree in Medical Education. Her academic interests include use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the ICU and assessment in medical education. She lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico with her husband Alex and cat Mozzum and she goes outside to play in the beautiful Rocky Mountains every free minute that she can. The parts of her brain that are not full of medical knowledge are full of Broadway song lyrics.