Contributed by Dafna Ofer, MD, Instructor, and Grace W. Pien, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

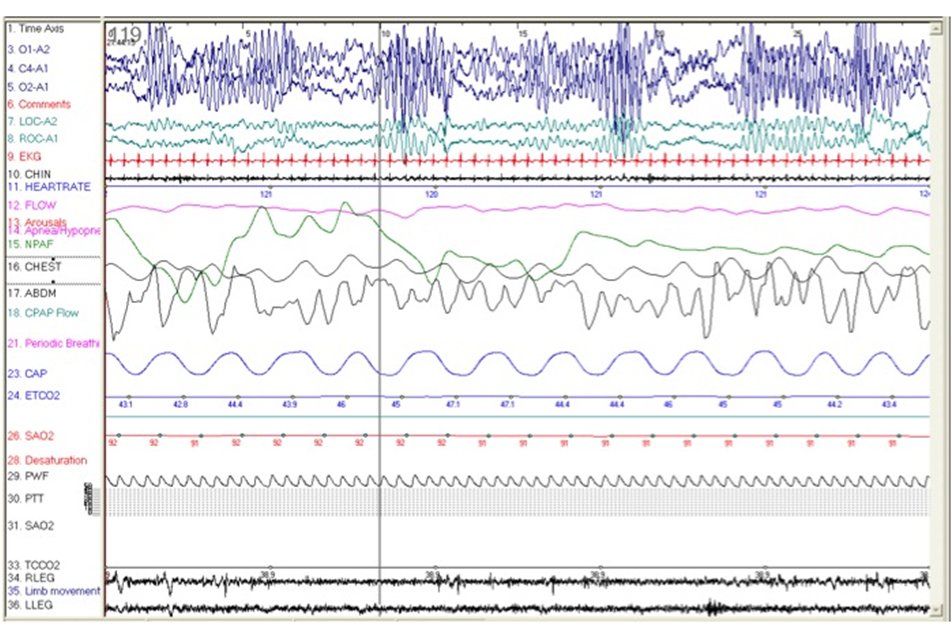

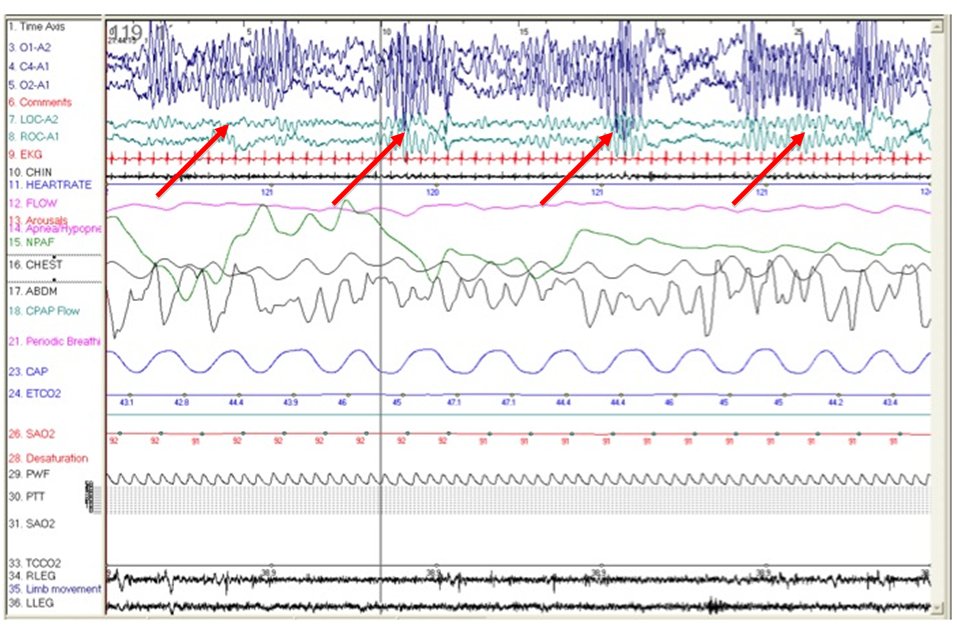

A 5-year-old boy with a history of ADHD and staring episodes is referred for evaluation of sleep-disordered breathing because of snoring, restless sleep and difficulties awakening in the morning. This 30-second epoch of stage N1 sleep was recorded during his overnight polysomnography. What is the finding in the following PSG fragment and its significance?

Answer: Hypnagogic Hypersynchrony (HH)

This epoch demonstrates bursts of Hypnagogic Hypersynchrony.

Hypnagogic hypersynchrony (see red errors in figure) is a common EEG finding in infants and children. Gibbs et al. were amongst the first to describe it in 1950. It usually occurs at sleep onset or during drowsiness, but can also occur upon awakening from sleep, when it is referred to as hypnopompic hypersynchrony. It is characterized by bursts of paroxysmal bilateral rhythmic activity. Hypnagogic hypersynchrony can be diffuse, appearing in all EEG channels. However, it is usually more prominent over the frontal (mid-frontal) leads. The typical frequency is 3-5 Hz. The amplitude can vary from lower than the surrounding EEG to as high as 350 mV, more commonly between 75-200 mV. The occurrence of hypnagogic hypersynchrony is abrupt and it can either be intermittent or continuous for several minutes.

Hypnagogic hypersynchrony is first seen at 2-4 months of age, and is observed in approximately 30% of normal infants at 3 months of age. At this time, it is most prominent over the central regions. The distribution widens by 8-12 months. Hypnagogic hypersynchrony is most frequently observed between 3-11 months. It is present in up to 95% of infants and children ages 6 months to 4 years. Thereafter, it gradually disappears, occurring in only 10% of children at 11 years and rarely seen after the age of 12 to 13 years.

Hypnagogic hypersynchrony most frequently occurs in stage N1 sleep, but can be seen in stage N2 sleep, when it is called theta hypersynchrony. It disappears in deeper stages of non-REM sleep. It can be mistaken for spike and wave or epileptiform discharges (generalized interictal epileptiform discharges). The key to distinguishing hypnagogic hypersynchrony from spike and wave activity is the lack of fixed location of the spike along the slow wave in HH, as well as the tendency of the slow waves in HH to have changing amplitudes, in contrast to the more uniform slow wave amplitude of generalized interictal epileptiform discharges (IED).

The phenomenon of hypnagogic hypersynchrony has no clinical significance. In the case presented here, the finding was incidental. Snoring and staring episodes in a child with a history of ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) are common complaints in children presenting to the sleep center for evaluation. In the majority of such cases, children undergo a sleep study to evaluate for sleep disordered breathing (SDB), as SDB may play a significant role in the child’s neuro-cognitive function, affecting behavior, learning and mood. (Hence, children with SDB are sometimes mistakenly diagnosed as having ADHD.) Staring episodes may raise suspicion for absence seizures, which can also mimic ADHD. Absence seizures typically occur in otherwise normal school-age children. They have a characteristic EEG finding of a 3-Hz generalized spike and wave complex (often more prominent in the fronto-central regions). The typical findings of absence seizures should not be confused with hypnagogic hypersynchrony.

In the 30 second epoch presented here, recorded close to sleep onset, a mildly irregular breathing pattern is observed. However, there is no clear evidence of sleep-disordered breathing in this epoch.

References:

- The Visual Scoring of Sleep and Arousal in Infants and Children. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007 Mar 15;3(2):201-40

- Clinical correlates of exceedingly fast activity in the electroencephalogram. Dis Nerv Syst. 1950;11:323-6.

- Atlas of EEG patterns. John M. Stern, MD; Jerome Engel, Jr., MD, PhD. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004

- Atlas of Sleep Medicine. Sudhansu Chokroverty; Robert J. Thomas; Meeta Bhatt. Elsevier. 2005

- Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, Fourth edition. Kryger; Roth; Dement. Elsevier. 2005

- Neurocognitive and behavioral impact of sleep disordered breathing in children. Judith A. Owens, MD MPH. Pediatric Pulmonology 44:417–422. 2009