Contributed by Don Hayes, Jr., MD, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Internal Medicine, and Surgery, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Director, University of Kentucky Pediatric Sleep Program Kentucky Children’s Hospital, Associate Director, University of Kentucky Healthcare Sleep Disorders Center C424, University of Kentucky Medical Center and Mark L. Splaingard, MD, Professor of Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Director, Pediatric Sleep Disorder Center, Nationwide Children’s Hospital

Answer:

- The patient diagnosis is obstructive sleep apnea.

- The patient should be referred for adenotonsillectomy.

Discussion

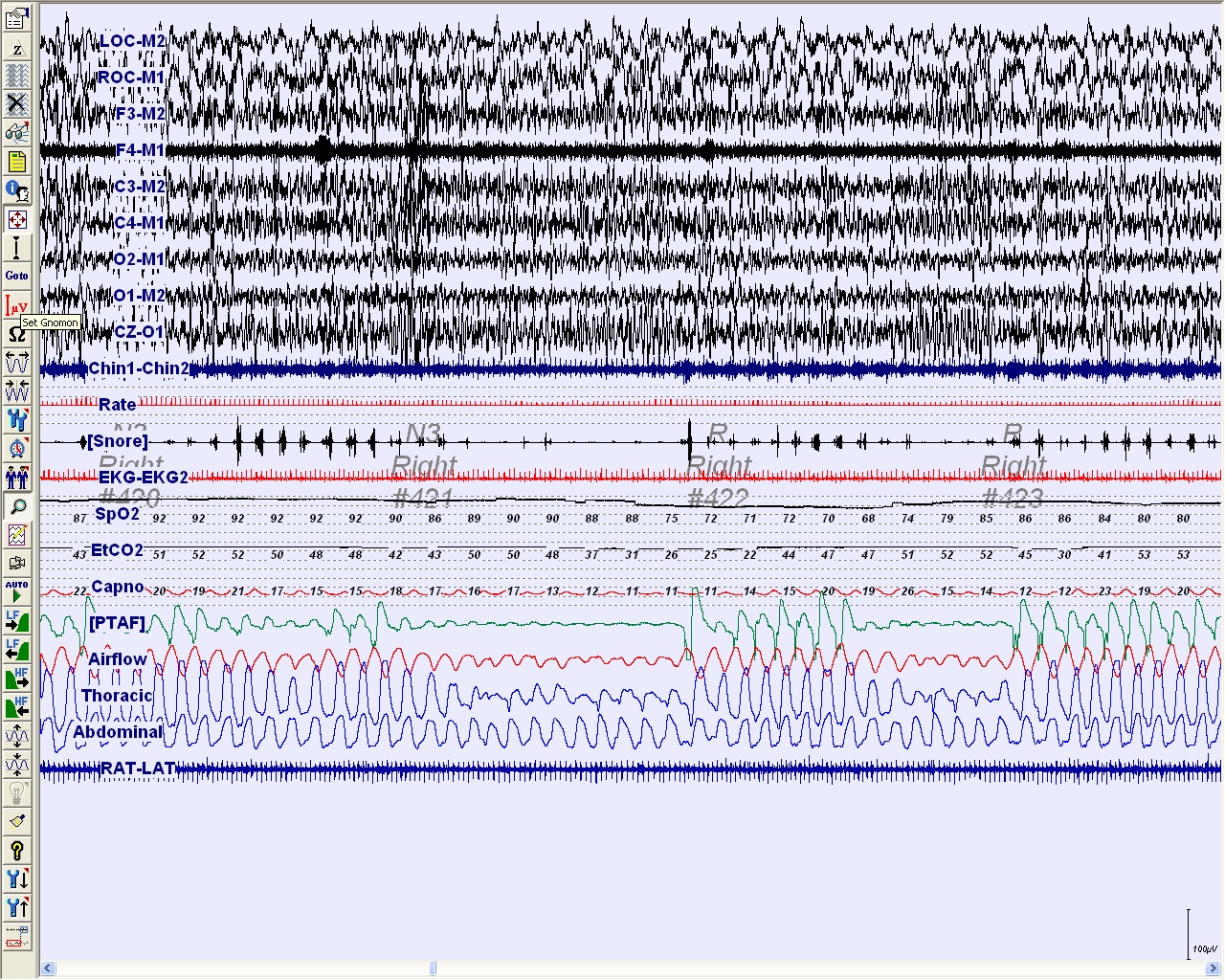

The patient had an elevated apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 21.5 events/hr of sleep with the lowest measured oxygen saturation at 68% (see panel A). He was subsequently referred to otolaryngology for adenotonsillectomy (AT) due to tonsillar hypertrophy. After surgical treatment, his daytime sleep was less prevalent, his snoring improved but did not completely resolve, and the nighttime arousals were less frequent.

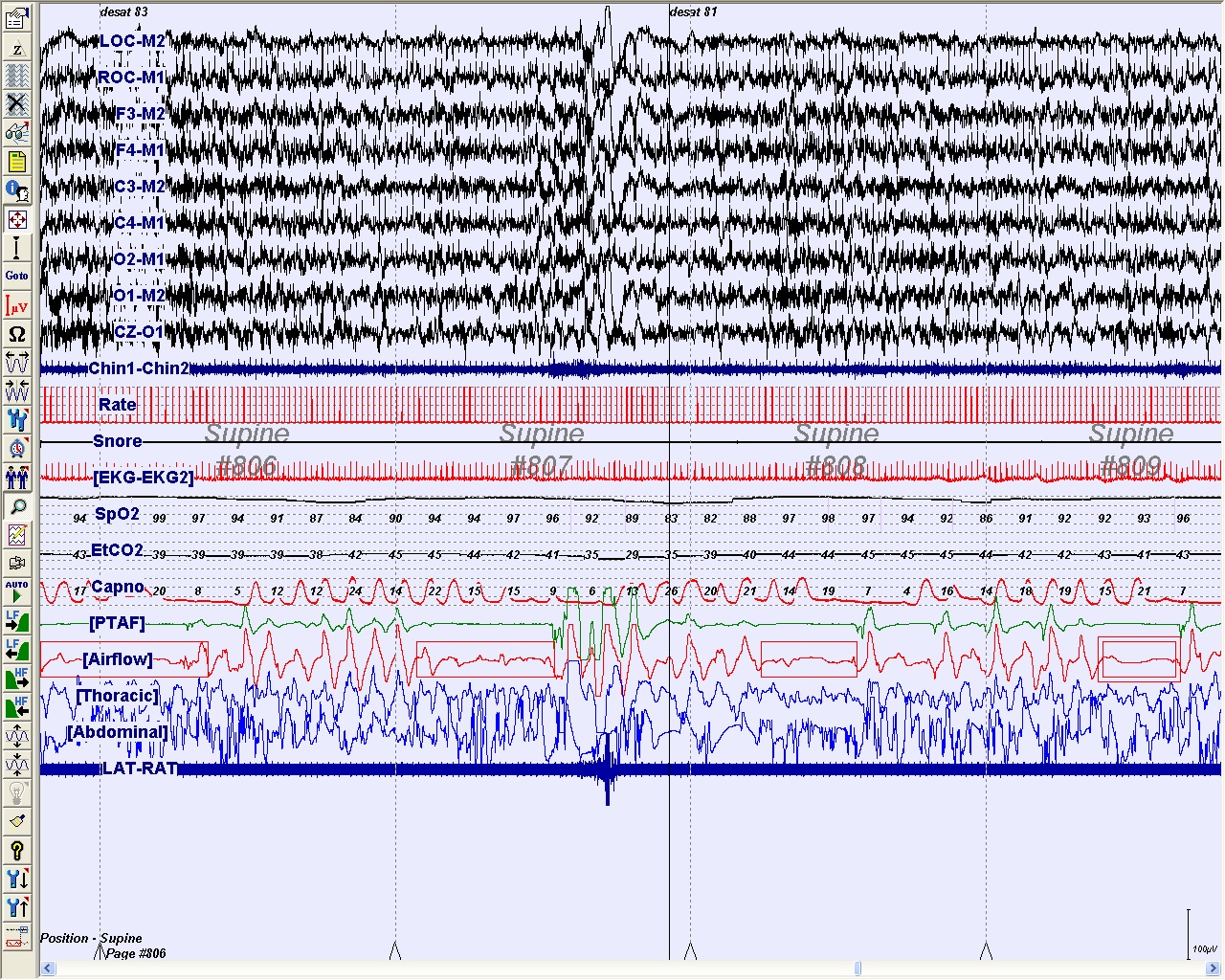

Panel B demonstrates a 2-minute epoch from a repeat nocturnal PSG that was performed 3 months after surgery. The AHI was persistently elevated at 12.6 events/hr of sleep with lowest measured oxygen saturation of 80%.

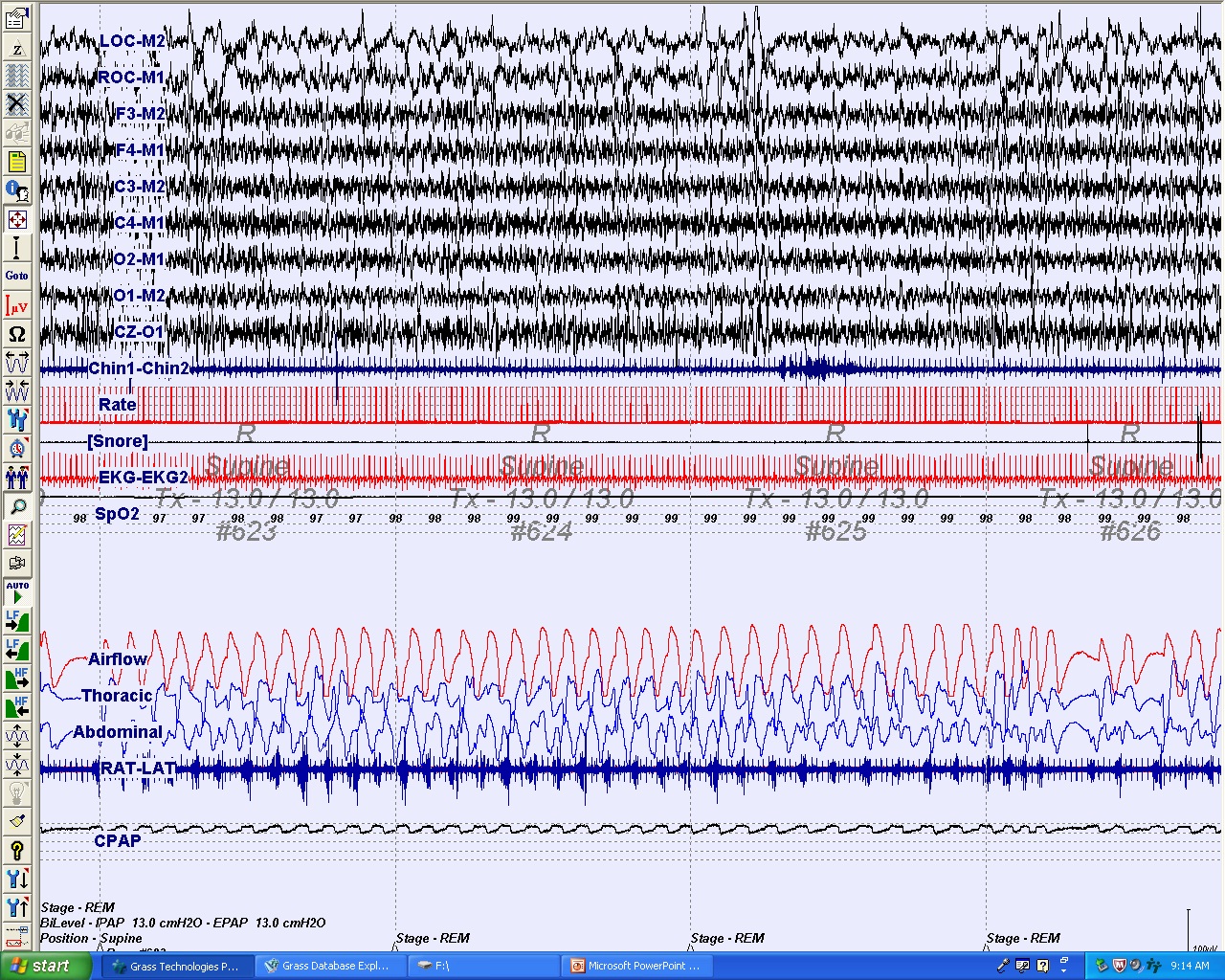

The patient was subsequently referred for a CPAP titration sleep study. Panel C demonstrates a 2-minute epoch of a nocturnal PSG for CPAP titration that identified an optimal treatment pressure of 13 cm H2O. This epoch demonstrates that CPAP treatment at 13 cm H2O was therapeutic while the patient is in rapid eye movement sleep and supine.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children is characterized by upper airway obstruction that disturbs sleep quality and may be associated with recurrent oxyhemoglobin desaturation or hypercapnia. Snoring is a common presenting symptom in children with OSA, but there are also other signs often reported by parents or care providers including daytime symptoms of hyperactivity, aggressive behavior, and excessive sleepiness; unusual sleep positions including neck hyperextension; movement arousals; excessive sweating during sleep; headache upon awakening; paradoxical chest wall motion during inspiration; secondary enuresis; and impaired growth (1). OSA is diagnosed based on a PSG with at least 1 scoreable respiratory event per hour of sleep with each event lasting at least 2 respiratory cycles in duration (1). Approximately 2% of children have OSA (2). OSA develops more commonly during early childhood between the ages of 2 and 8 years when adenotonsillar size is largest relative to size of the airway (3).

Adenotonsillectomy (AT) improves obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children by increasing the upper airway patency. The benefit of AT has been suggested based several meta-analyses of uncontrolled studies. (4, 5). Contrary to popular belief, AT often is not curative but offers significant improvements in the AHI, making it a valuable first-line treatment for OSA in children (4, 5). One study demonstrated that AT yielded complete normalization only in 25% of the children with OSA (6).

Factors that promote incomplete resolution to surgical treatment remain unclear. A recent multicenter retrospective study in the United States and Europe of 578 healthy children undergoing AT for OSA identified residual disease in a large proportion of children despite surgical treatment, particularly in children over 7 years of age or obese children (7). The investigators also discovered that the presence of severe OSA in non-obese children or chronic asthma necessitated a recommendation of a post-AT nocturnal PSG due to higher risk for residual OSA (7).

The Randomized Controlled Study of Adenotonsillectomy for Childhood Sleep Apnea (CHAT) is the first randomized controlled study to evaluate the current standard of OSA treatment in children. The study is funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and includes 6 major academic centers recruiting children ages 5 to 9 with large tonsils and adenoids who have breathing problems during sleep. The participants are randomized into 2 groups with the early treatment group undergoing AT within 1 month after enrollment and the other group being re-evaluated for surgery after a 7-month waiting period. Results of the study have not yet been published.

This case illustrates residual clinical symptoms in a child with OSA after surgical treatment; however, this may not be the case for all patients. The current evidence in the medical literature does not clearing define what children with OSA should undergo repeat PSG after AT. Close follow-up should be encouraged and repeat PSG should be considered for children with craniofacial anomalies and neuromuscular disorders since these children are at higher risk for residual OSA. Repeat PSG also could be considered in older children, children who are obese, non-obese children with severe OSA, or children with asthma depending on clinical course after surgical treatment. The CHAT study may provide even more insight into the treatment of children with OSA once it is completed.

References

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. 2nd ed. Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

- Marcus CL. Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:16-30.

- Hoban TF. Sleep disorders in children. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1184:1-14.

- Brietzke SE, Gallagher D. The effectiveness of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in the treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134:979-84.

- Friedman M, Wilson M, Lin HC, Chang HW. Updated systematic review of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy for treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140:800-8.

- Tauman R, Gulliver TE, Krishna J, Montgomery-Downs HE, O'Brien LM, Ivanenko A, Gozal D. Persistence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children after adenotonsillectomy. J Pediatr 2006;149:803-8.