Contributed by Sameh S. Morkous, MD, FAAN Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Neurology Division, Lehigh Valley Children’s Hospital, Allentown, PA. Assistant Professor of Pediatrics Core Academic Rank, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida. Clinical Professor at DeSales University. Corresponding Author: Sameh S. Morkous, MD, FAAN Children’s Hospital at Lehigh Valley Department of Pediatrics 1210 S. Cedar Crest Blvd., Suite 2400 Allentown, PA 18103-6229 Phone: 610-402-3888 Fax: 610-402-3892 Email: samehserry20@hotmail.com

A 5-year-old girl presented to a pediatric sleep laboratory for polysomnography to address the referring physician’s suspicion for obstructive sleep apnea. During the sleep study, the technician noticed that the child stared for 10 to 15 seconds, became unresponsive, and flickered the fingers of her left hand as she fell asleep (Video 1).

This behavior had also been observed by the child’s mother, who thought it to be part of a habitual self-soothing behavior.

There was no recall of similar events during the day and no report of tongue biting or bladder or bowel incontinence, but occasional brief episodes of staring had been observed. There was no significant medical history. Her body mass index was 17.29 kg /m2. Examination revealed a Mallampati score of 2 and a tonsil size of 2+. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

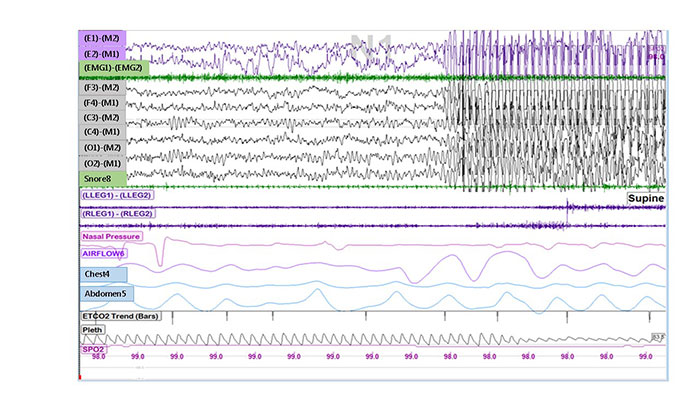

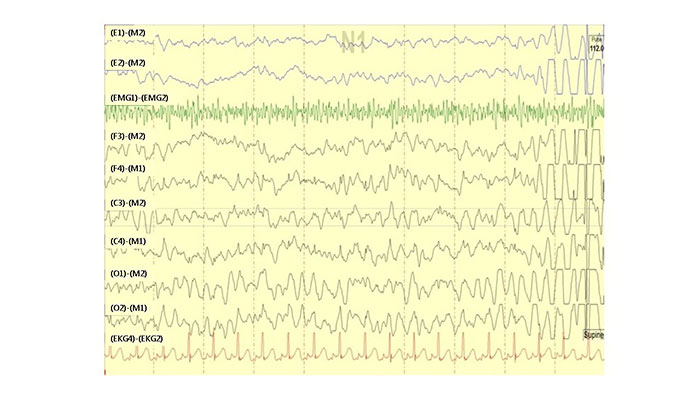

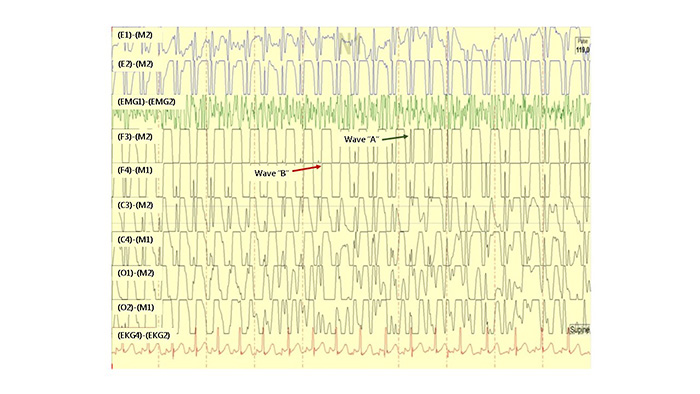

Polysomnography revealed a sleep efficiency of 92.2% with a sleep latency of 16 minutes, total sleep time of 544 minutes, wake time of 15 minutes and an arousal index of 14 events per hour. The total apnea-hypopnea index was 6 events per hour. The lowest oxygen saturation was 85% and the mean end-tidal CO2 was 23 mmHg. The periodic limb movement index was 0.0 events per hour. Figures 1 – 3 represent 30 and 10 second epochs from the patient’s polysomnogram during the observed finger-flickering event. The event observed was not related to obstructive respiratory events.

Questions

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What is the most appropriate next step in the management of this patient?

Discussion

Incidental paroxysmal spells were discovered in a 5-year-old girl during the wake-sleep transition phase of an overnight sleep study for evaluation of suspected obstructive sleep apnea. The electroencephalography (EEG) recordings showed classic 3 hertz (Hz) spike-and-slow wave epileptiform discharges simultaneously as the child was observed staring for several seconds and flickering her fingers.

The differential diagnosis of paroxysmal events during sleep includes NREM arousal disorders (confusional arousals, sleep walking and sleep terrors), REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), sleep-related movement disorders, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, and frontal or temporal lobe seizures (1). Sleep terrors are usually distinguished by associated features like tachycardia and diaphoresis and the subsequent lack of recall. Nocturnal frontal lobe seizures are stereotypical, of short duration, tend to cluster, and are associated with hypermotor activity. In our case, RBD can be ruled out because the event happened at the wake-sleep transition, not during REM sleep.

Several clues from the history point toward absence seizures, including the brief staring duration, the lack of a postictal phase, the stereotypical presentation, and the classical EEG finding. Typical absence seizures begin abruptly, last 10 to 30 seconds, and resolve spontaneously. The EEG will show the typical 3 Hz spike-and-slow wave. Atypical seizures are similar, except they tend to have a less abrupt onset with more pronounced changes in tone. In atypical absence seizures, the ictal EEG will show 1.5 to 2.5 Hz slow spike-and-wave or multiple spike-and-wave discharges (2).

In our patient, brief 3 Hz epileptiform discharges were seen occasionally during sleep in stages N1 and N2 but were not associated with obstructive respiratory events or motor activity. In a study by Sadleir and colleagues that analyzed the electroclinical features of absence seizures during sleep, 30 children with genetic generalized epilepsy had 52 paroxysms of generalized spike-and-wave epileptiform discharges more than 2 seconds during sleep (3). Only 18/52 (35%) demonstrated a clinical sign. The consequences of the 3 Hz spike-and-slow wave epileptiform discharges awake and asleep on development and seizure freedom is unknown. However, the goal should be to reduce the burden of seizures, awake and asleep.

Treatment is indicated. In a study by Glauser and associates, ethosuximide and valproic acid were more effective than lamotrigine in the treatment of childhood absence epilepsy (4). Ethosuximide was associated with fewer adverse attentional effects and is the treatment of choice. Strengths of that study include the prospective, randomized study design, stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, utilization of EEG to determine seizure freedom, and clearly defined criteria for treatment failure. In contrast, the sodium channel blockers, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and oxcarbazepine, as well as other antiepileptic drugs including gabapentin, pregabalin, tiagabine, and vigabatrin, may exacerbate absence seizures.

Children with epilepsy have a higher prevalence of sleep breathing disorders compared to healthy children. The surgical treatment of sleep apnea has been found to reduce seizure frequency (5). Treating the underlying sleep apnea will increase the chance of seizure control.

This case illustrates the importance in recognizing paroxysmal events during sleep studies by the sleep technician and physicians both referring for and interpreting sleep studies.

Answers

-

What is the most likely diagnosis?

The most likely diagnosis is absence seizures. -

What is the most appropriate next step in the management of this patient?

The most appropriate next step is to confirm the diagnosis and to start the patient on an antiepileptic medication (ethosuximide).

Follow-Up

An ambulatory, 48-hour EEG showed intermittent generalized 3 Hz spike-and-slow wave epileptiform discharges mainly while awake and occasionally during sleep. These discharges were associated with frequent staring spells that lasted for 20 to 30 seconds while awake. Because finger flickering was observed only on the left side, brain MRI was performed and was normal.

The patient was started on ethosuximide and, at the 3-month follow-up, her spells had stopped. She was also diagnosed with mild to moderate sleep apnea and referred to Ear, Nose & Throat for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy.

References

-

Boursoulian LJ, Schenck CH, Mahowald MW, Lagrange AH. Differentiating parasomnias from nocturnal seizures. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8:108-112.

-

Holmes GL, McKeever M, Adamson M. Absence seizures in children: clinical and electroencephalographic features. Ann Neurol 1987;21:268-273.

-

Sadleir LG1, Farrell K, Smith S, Connolly MB, Scheffer IE. Electroclinical features of absence seizures in sleep. Epilepsy Res 2011;93:216-220.

-

Glauser TA, Cnaan A, Shinnar S, Hirtz DG, Dlugos D, MasurD, Clark PO, Adamson PC; Childhood Absence Epilepsy Study Team. Ethosuximide, valproic acid, and lamotrigine in childhood absence epilepsy: initial monotherapy outcomes at 12 months. Epilepsia 2013;54:141-155.

- Gogou M, Haidopoulou K, Eboriadou M, Pavlou E. Sleep apneas and epilepsy comorbidity in childhood: a systematic review of the literature. Sleep Breath 2015;19:421-432.