Contributed by C-H Yoon, R L Riha, Department of Sleep Medicine, Royal Infirmary Edinburgh, Scotland

A 19 year-old female with mild hayfever and irritable bowel syndrome presented with a several year history of fatigue, variable sleep duration and longstanding sleep onset insomnia.

- Her Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was 0/24 (mother’s assessment: 0/24).

- Her body mass index was 26.9 kg/m2, and her airway was classified Mallampati Grade I. There was no obvious retrognathia.

- She had no history of hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations, REM sleep paralysis, or cataplexy.

- She had not witnessed any apnoeic episodes and did not snore.

- There was no history of psychological problems or of depression / anxiety.

Question

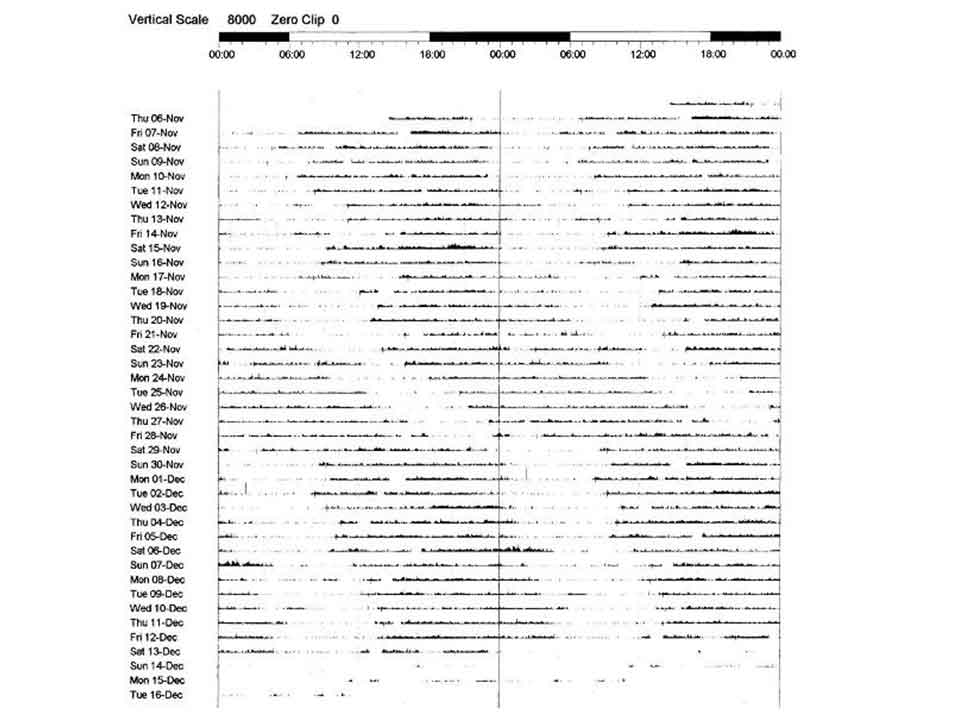

What is the underlying disorder responsible for the patient’s actigraphy trace below?

(Hint: the condition is exceedingly rare in sighted individuals.)

Non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome (free-running disorder) in a sighted individual.

Discussion

There was no suggestion on history or examination of narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome, sleep paralysis or idiopathic hypersomnia.

The irregular sleep-wake times and complaint of sleep-onset insomnia suggested a circadian rhythm disorder and the initial investigation was actigraphy with simultaneous sleep diaries filled in by the patient.

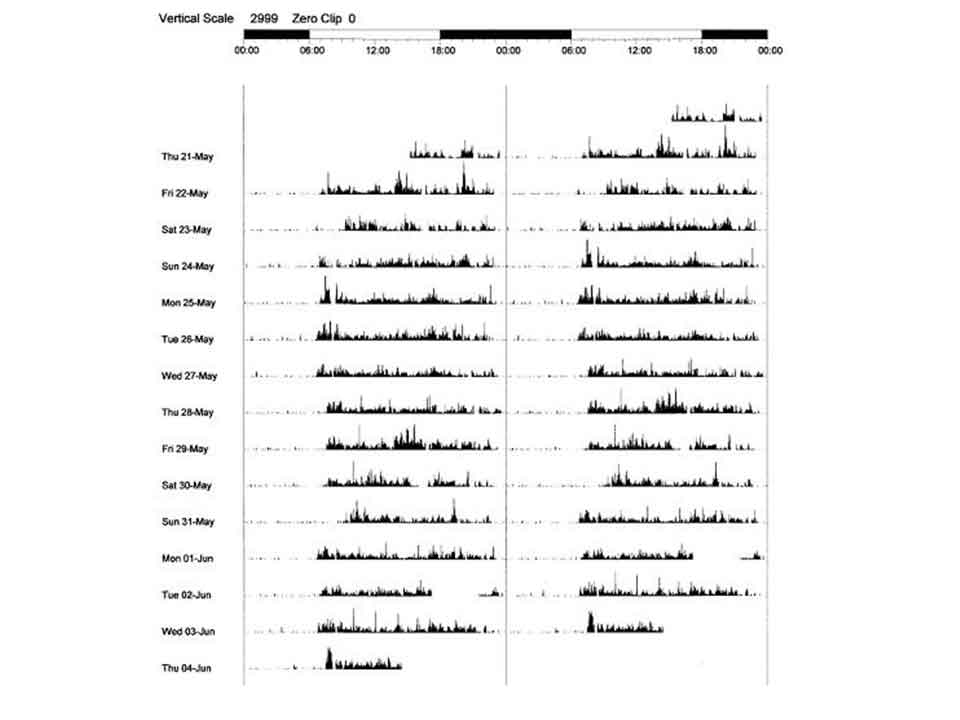

Compare the patient’s actigraphy with Figure 2. which is an actigraph trace of a typical entrained 24-hour sleep-wake pattern. Note the progressive temporal transposition of the sleep onset time in the patient’s actigraph (as indicated approximately by the first point of a relatively inactive period) - the aslant pattern is indicative of a classical free-running disorder, which is associated with an intrinsic circadian period of greater than 24 hours. This is not unlike the consequence of being in a time-free environment bereft of zeitgebers (such as in totally blind individuals).1,2

Diagnostic criteria for this disorder have been outlined in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) as follows:3

- Primary complaint of either sleep onset insomnia or excessive sleepiness related to the inability to maintain stable entrainment to a 24-hour sleep-wake pattern.

- ≥1 week of completed sleep diaries (± actigraphy) demonstrating a pattern of progressive delays in sleep and wake times with every subsequent day (endogenous circadian period t > 24 hours).

- The sleep problems cannot be better explained by another sleep, neurological or psychiatric disorder, other pathology, or by drug / substance use disorder.

Further noteworthy features of the condition were described in a large-cohort study of free-running disorder (FRD) in sighted individuals (n=57):4

- FRD is much more common in males and in the blind.

- This circadian rhythm sleep disorder tends to commence during the teenage years (as with this patient).

- Delayed sleep phase syndrome (characterised by a consistent sleep schedule that is significantly later than the conventional or desired time)5 and psychiatric problems preceded the symptoms of FRD in 26% and 28% of the subjects respectively. In this case, the patient had been previously diagnosed with DSPS (DSPS can also present with progressive delays in sleep onset for several days, particularly in its initial stages, and should be included in the differential diagnosis for FRD).

- Ninety-four percent of the 28% with premorbid psychiatric problems experienced secondary social withdrawal, suggesting this to be an important aetiological factor in the pathogenesis of FRD.

- The aetiology and pathogenesis of FRD remain enigmatic but risk factors include cranial trauma6, dementia7 and mental retardation8 (neurological compromise potentially leading to failure to process exogenous temporal cues).

Diagnostic tools:9

- Sleep diaries / logs to ascertain the sleep pattern(s). Supported by committee consensus.

- One level 2 and seven level 4 studies in sighted individuals substantiate the long-term measurement of circadian phase markers e.g. melatonin rhythm as a means by which to diagnose FRD.

- Actigraphy for several weeks if possible.

- Psychiatric review – in this 19-year old patient, a formal psychiatric review has not been conducted since the diagnosis of FRD; it may be worth doing so notwithstanding the clinical impression of psychiatric normality.

Treatment:9

- Provide a potent zeitgeber via timed light exposure in the morning to shift the circadian phase – five level 4 reports support this.

- Four Level 4 reports indicate the efficacy of timed melatonin administration (a few hours before bedtime) to correct the circadian phase.

- Prescribed sleep-wake scheduling.

- There is conflicting evidence for the administration of vitamin B12 (oral or intramuscular) as a potential stimulus for correct entrainment, although the physiological basis for this is undetermined. The patient in this case report was found to have low serum B12 (likely secondary to oral contraceptive pill use), and her mother has pernicious anaemia.

- In this patient, FRD has profoundly disrupted her educational and social development, although the use of her computer has enabled her to interact with her peers via the internet. She also has a boyfriend.

- The rarity of the condition amongst sighted individuals has resulted in very few treatment studies, and further work will be necessary to establish the respective efficacies of the above treatments. What is certain is that sustained treatment is of paramount importance if one is to avert a relapse of an aberrant circadian rhythm.

References

1Czeisler, CA, Duffy, JF, Shanahan, TL, et al. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science 1999;284:2177-81

2Sack, RL, Lewy, AJ, Blood, ML, Keith, LD, and Nakagawa, H. Circadian rhythm abnormalities in totally blind people: incidence and clinical significance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75:127-34

3American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic & Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005

4Hayakawa, T, Makoto Uchiyama, M, Kamei, Y, et al. Clinical Analyses of Sighted Patients with Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Syndrome: A Study of 57 Consecutively Diagnosed Cases. Sleep 2005;28:945-952

5Sack, RL, Dennis, A, Auger, RR, et al. Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders: Part II, Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder, Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder, Free-Running Disorder, and Irregular Sleep-Wake Rhythm. Sleep 2007;30:1484-1501

6Boivin, B, James, FO, Santo, JB, et al. "Non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome following a car accident." Neurology 2003;60:1841-3

7Motohashi, A, Maeda, A, Wakamatsu, H, et al. Circadian rhythm abnormalities of wrist activity of institutionalized dependent elderly persons with dementia J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci 2000;55A:M740-M743

8Okawa, M, Nakajima, S, Sasaki, H, et al. A case with free-running of the sleep-waking rhythm and successful non-drug treatment by forced awakening. Sleep Res 1980; 9:215

9Morgenthaler, TI, Lee-Chiong, T, Alessi, C, et al. Practice Parameters for the Clinical Evaluation and Treatment of Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders. Sleep 2007;30:1445-1459