Slow winds in a dark and starry night

Andres Herrera-Camino MD1,2, Ferdinand Coste DO2, Mai He MD PhD3, Jennifer Duncan MD1

1 Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis

2 Division of Pediatric Pulmonary Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis

3 Division of Pediatric Pathology, Washington University in St. Louis

Intro:

An 11-year-old female presented to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for evaluation and management of hypoxemia. Two months prior to admission the patient was evaluated for an acute respiratory illness associated with a submandibular mass. The initial chest x-ray (CXR) showed diffuse pulmonary nodules and an infectious work-up was negative. Her respiratory symptoms resolved; however, her submandibular mass persisted. She was scheduled for an MRI of the neck on the day of admission and was noted to have significant hypoxemia. She was ultimately transferred to the PICU for oxygen therapy. CXR on PICU admission demonstrated the following:

Figure 1: Chest radiograph

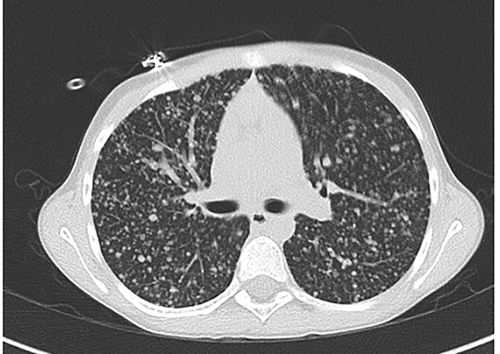

The patient underwent an extensive evaluation for the disseminated pulmonary nodules seen on the CXR (Fig 1), including a Chest CT scan (Fig 2):

Figure 2: Chest CT scan

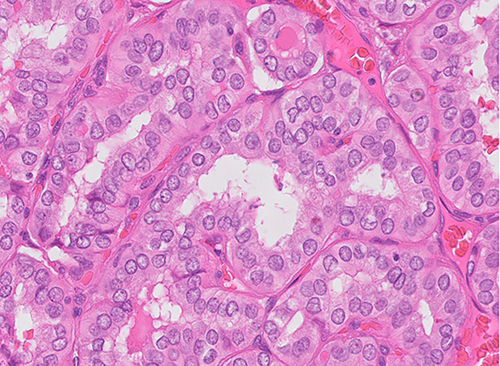

Prior to admission, the patient had undergone an ultrasound examination of the submandibular mass which was suggestive of a vascular soft tissue mass. Due to concern for bleeding, a biopsy of this site was deferred and the decision was made to perform an open lung biopsy which revealed the following (Fig 3):

Figure 3: Histopathology

Question:

What is the diagnosis?

- Miliary Tuberculosis

- Fungal infection

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Disseminated malignancy

Answer

5. Disseminated malignancy

Metastatic Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

Differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) almost exclusively presents as papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) in children and adolescents. It is a rare disease and it accounts for approximately 1.4% of all pediatric malignancies1,2.

Exposure to external or internal radiation are well documented risk factors for the development of thyroid carcinoma. Prolonged elevation of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), the presence of thyroid-stimulatory immunoglobulins in Grave’s disease and associations with Hashimoto’s disease have also been implicated as potential risk factors in adults. However, direct causative relationships between these diseases and PTC remain poorly documented, especially in the pediatric population1,2.

Children, as opposed to adults, often present with lymph node or disseminated lung metastases (known as miliary metastases). PTC should be suspected in children with a growing thyroidal nodule or a persistent lymph node in the neck. Diagnostic procedures include thyroid ultrasound, fine-needle biopsy and diagnostic hemithyroidectomy in some cases3. Classic histopathologic findings include a typical papillary pattern, ground glass nuclei, nuclear groove and colloid deposition (Fig 3)4.

The absence of granulomas in tissue excluded the diagnoses of both infectious and/or noninfectious granulomatous lung diseases such as tuberculosis, fungal infections or sarcoidosis. Special stains and cultures of tissue biopsy also failed to identify any pathogens as the cause of the pulmonary nodules. The diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis was also excluded based on the lack of features of interstitial lymphocytic infiltrates and fibrosis, edema, noncaseating granulomas, foamy macrophages and bronchiolitis obliterans.

Despite the relatively high rate of nodal and distant metastases, prognosis is very favorable with long term survival rates of over 95% in children and adolescents 3.

Since pediatric PTC is a comparatively rare disease, most treatment options for this patient population are derived from experiences in the adult PTC population3. Treatment options for PTC depend on the stage of the disease and degree of extrathyroid extension or lymph node metastases3. For advanced disease with lung metastases, total thyroidectomy, node dissection, radioiodine therapy, and TSH suppression therapy are recommended to minimize disease recurrence4. The use of extended surgery does increase the potential risk for surgical complications such as recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury or permanent hypoparathyroidism. A more conservative approach with lobectomy for localized tumor may be a suitable option for patients with early-stage disease3.

This patient received complete thyroidectomy followed by radioactive iodine therapy and thyroid hormone replacement. After radioiodine therapy, she developed respiratory insufficiency due to radiation pneumonitis for which oral steroid therapy and supplemental oxygen were initiated. The patient currently remains on oxygen therapy at home via nasal cannula/face mask and has moderate exercise limitation. Chest imaging studies still reveal signs of metastatic lung disease. Repeat radioactive iodine therapy with the goal of achieving remission is currently scheduled.

References:

-

Vaisman F et al. Thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents-systematic review of the literature. J Thyroid Res. 2011;845362.

-

Grigsby PW et al. Childhood and adolescent thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 2002 Aug 15;95(4):724-9.

-

Verburg FA et al. Pediatric papillary thyroid cancer: current management challenges. Onco Targets Ther. 2016 Dec 28;10:165-175.

-

Wada N et al. Pediatric differentiated thyroid carcinoma in stage I: risk factor analysis for disease free survival. BMC Cancer. Sep 1;9:306.