‘Sawing logs’ on spirometry or ‘A ‘Fluttering PFT’?

Kunal Jakharia, MD, Fellow, Division of Pulmonary Diseases and Critical Care Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

M. Leigh Anne Daniels, MD MPH, Clinical Instructor, Division of Pulmonary Diseases and Critical Care Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Introduction:

A 52-year-old male with hypertension, chronic kidney disease, COPD, and obesity (BMI of 31 kg/m2) presented to a primary care physician to establish care. He endorsed good compliance with ICS/LABA plus LAMA for his presumed clinical diagnosis of COPD, despite one exacerbation in the last year. He reported mild morning headaches and some daytime fatigue. He denied any voice changes or hoarseness.

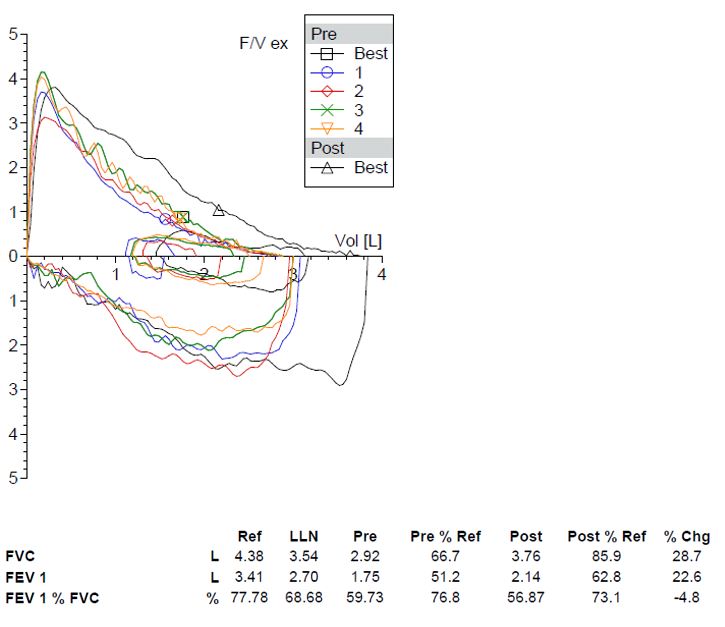

Spirometry performed pre-and post-bronchodilator is shown below.

Question:

In addition to obstructive pathology, what do these PFTs suggest?

- Variable intrathoracic obstruction

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Fixed upper airway obstruction

- Poor bronchodilator response

B. Obstructive sleep apnea

Discussion:

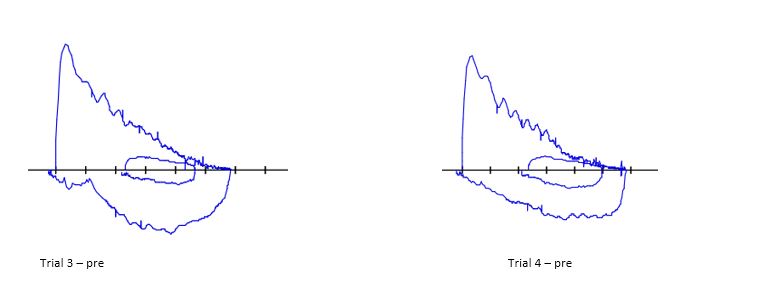

This patient’s flow volume (FV) loop has a classic saw-tooth pattern with oscillations in both the inspiratory and expiratory curves. It was previously thought that this saw-tooth pattern could be attributed to artifacts in the resonance frequency from the spirometry equipment (1). Later, these flow oscillations were seen more commonly in patients with sleep-disordered breathing and those with upper airway abnormalities. Although the sensitivity of the saw-tooth pattern for OSA is low (11%), some studies demonstrated specificities as high as 94% (2) while others failed to replicate it (3). However, it has also been described in 31% of individuals who snore but do not carry a diagnosis of sleep apnea, as well as in 10% of normal individuals (2). The presence of this pattern has not shown to correlate with AHI or other metrics of severity in OSA (3).

The oscillations are defined as a reproducible sequence of alternating decelerations and accelerations of flow creating a ‘saw-tooth’ pattern; this pattern is superimposed on the patient’s baseline contour of the FV loop (4). They can occur in any portion of the FV loop. The saw-tooth pattern can also be present in a variety of conditions affecting the upper airway. Fluttering and tremors are thought to be the two general mechanisms causing these oscillations on the FV loops. Turbulence is caused by flaccidity of upper airway structures due to low muscle tone or increased unsupported adipose tissue. This leads to fluttering of the redundant tissue during inspiration and expiration causing oscillations (4). Tremors of glottis and supraglottic structures can also produce oscillations of the FV loop, however they are generally low in frequency. These tremors are generally neurological in origin and do not arise from turbulence.

Common causes of the saw-tooth pattern due to turbulence (4):

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Upper airway tumors/obstruction

- Upper airway burn injuries (due to damage to the supporting structures of upper airways)

- Tracheobronchomalacia

- Snorers without OSA

Common causes of saw-tooth pattern due to tremors (4):

- Parkinson's disease

- Neuromuscular disorders with bulbar involvement

- Laryngeal dyskinesia

- van Leeuwenhoek’s disease (rare disorder characterized by rapid, involuntary diaphragmatic contractions)

Posture can be an important factor in saw-toothing of the FV loop. The sensitivity of this pattern to detect OSA increased from 11% in sitting position to nearly 40% in supine position (5). This re-enforces the concept that loose unsupported tissue plays a role in the oscillations.

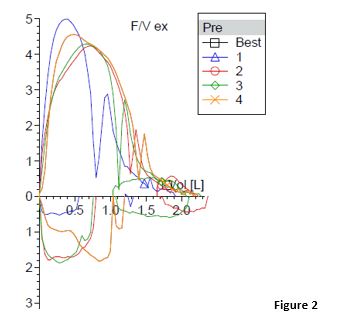

A similar pattern can be seen when a patient frequently coughs (Figure 2) or tries to produce a sound during the maneuver. However, it is not reproducible in each attempt. In contrast, the saw-tooth pattern is reproducible in the causes listed above and does not impact the accuracy of the PFT either.

Our patient underwent a polysomnogram and was diagnosed with moderate obstructive sleep apnea. An ENT evaluation ruled out laryngeal and vocal cord dysfunction and upper airway tumors.

References:

- Zamel N. Flow volume curve: the "saw-tooth" sign. Eur J Respir Dis 1986; 69:73.

- Katz I, Zamel N, Slutsky AS, et al. An evaluation of flow-volume curves as a screening test for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 1990; 98:337.

- Ashraf M, Shaffi SA, BaHammam AS (2008) Spirometry and flow-volume curve in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Saudi Med J 29:198–202

- Vincken WG, Cosio MG. Flow oscillations on the flow-volume loop: clinical and physiological implications. Eur Respir J 1989; 2: 543-549.

- Shore ET, Millman RP. Abnormalities in the flow-volume loop in obstructive sleep apnea sitting and supine. Thorax 1984; 39: 775-779.