Reading between the lungs

Sushilkumar Satish Gupta1 M.D., Carolyn Bendor-Grynbaum2 M.D., Benhoor Shamian1 M.D., Shyam Shankar1 M.B.B.S.

1Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

2Department of Internal Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Case:

A 20-year-old gravida 1 para 1 female was admitted to our hospital one day status-post normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was without complications and she delivered at 40 weeks and 5 days gestational age. The delivery was preceded by forceful and prolonged pushing. After the delivery, she developed acute chest pain, moderate in intensity, described as a pressure-like sensation, exacerbated by deep breaths, and radiating around her neck. The pulmonary service was consulted to evaluate the patient for these symptoms. She was afebrile and oxygen saturation was 97-100% on room air. Complete blood count showed leukocytosis to 17.8K/UL with neutrophil predominance, hemoglobin of 14.3gm/dl, serum chemistry was unremarkable. A physical exam revealed bilateral lung fields clear to auscultation bilaterally, without crackles or rhonchi and no murmurs or gallops on cardiac exam. She was found to have crepitus felt on palpation of her neck.

Question:

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Pneumomediastinum

- Pneumothorax

- Amniotic fluid embolism

- Pneumopericardium

A. Pneumomediastinum

Discussion:

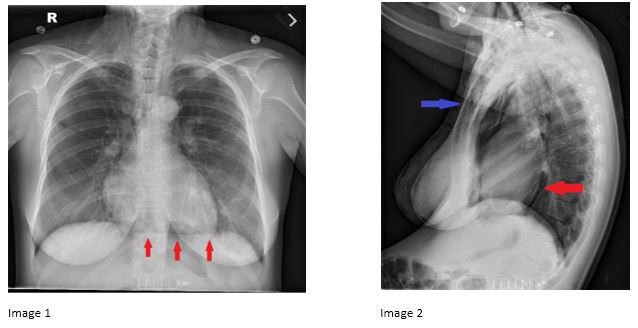

The patient was found to have spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) immediately following spontaneous vaginal delivery. Her chest radiograph revealed a continuous diaphragm sign, indicative of pneumomediastinum (Image 1, red arrows) on AP view. Lateral film (Image 2) revealed pneumomediastinum (red arrow) and subcutaneous emphysema (blue arrow).

SPM has been described in the literature, occurring 1 in 7000 to 45,000 patients. (1,2) It occurs most often in young patients, with a median age of 30 (interquartile range 20-69 years). (2)

While secondary pneumomediastinum occurs due to an identifiable predisposing event, such as intrathoracic infections, esophageal rupture, or trauma to the anterior chest wall, SPM usually occurs due to sudden increase in intrathoracic pressure that results in rupture of the alveoli. The released alveolar air centripetally dissects through the pulmonary interstitium along the bronchovascular sheaths toward the pulmonary hila, into the mediastinum. This is known as Macklin effect. (3)

Patients most often present with retrosternal chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, or dysphagia. Physical exam may reveal subcutaneous emphysema, as well as crepitus that is more audible with each heartbeat, known as Hamman’s sign. (4)

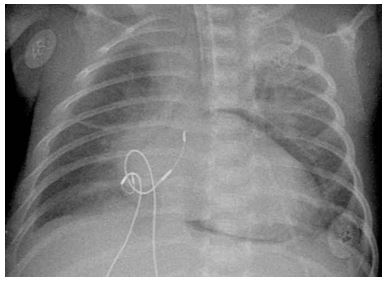

Pneumomediastinum often presents radiographically as the continuous diaphragm sign on chest radiography. The sign was first described by B Levin in 1973, and is identified as air seen between the inferior heart border and the superior surface of diaphragm. More specifically, the continuous diaphragm sign, as seen in our patient, appears as a continuous section of air and represents air entrapment posterior to the pericardium. An important diagnostic distinction is to differentiate pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum, in which air will be visualized only along the pericardial sac and it typically appears as an isolated broad band around the heart (Image 3), instead of extending beyond the length of the heart in pneumomediastinum. (5)

Image 3: Pneumopericardium, which must be distinguished from pneumomediastinum

Case courtesy of Radswiki, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 11794

Management of pneumomediastinum is usually conservative and it includes bed rest, analgesia, avoidance of strenuous physical activity, and supplemental oxygen to absorb free air in the mediastinum. Prognosis is usually favorable. Our patient was discharged home. A follow-up chest radiograph in two weeks showed complete resolution of pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema.

Although this condition is not catastrophic, prompt recognition is essential. Physicians should maintain heightened awareness for the continuous diaphragm sign.

References:

-

Aujayeb A, Miller J, Weatherhead M, et. al. Four cases of pneumomediastinum. Breathe 2015; 11(4). doi:10.1183/20734735.009715.

-

Iyer VN, Joshi AY, Ryu JH. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: analysis of 62 consecutive adult patients. Mayo Clin Proc 2009; 84(5): 417–21.

-

Macklin MT, Macklin CC. Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiment. Medicine 1944; 23: 281–358.

-

Alexandre AR, Marto NF, Raimundo P. Hamman’s crunch: a forgotten clue to the diagnosis of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. BMJ Case Reports 2018: bcr-2018-225099.

-

Bejvan SM, Godwin JD. Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs. Am J Roentgenol 1996; 166: 1041–8.