Hiding in Plain Sight

Masooma Aqeel, MD 1; Jayshil J. Patel, MD 2

1 Assistant Professor, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

2Associate Professor, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA

Case:

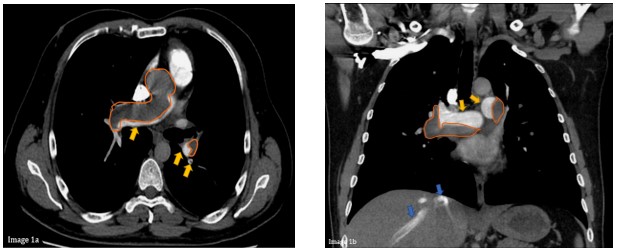

A 42-year-old non-smoking male presents with 6-months of fatigue, progressively worsening dyspnea and scant hemoptysis. Physical examination reveals resting room-air oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 92%, jugular venous distention (JVD) (11 cm H2O above right atrium), a loud pulmonic component of the 2nd heart sound (P2), S4 gallop, a left parasternal (right ventricular (RV)) heave and left leg pitting edema (1+). Lungs are clear. Echocardiography suggests severe pulmonary hypertension and severely reduced RV function. Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) reveals:

Question:

What is the first-line treatment for this condition?

- Pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA)

- Lifelong anticoagulation

- Supplemental oxygen, diuretics and spironolactone

- Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)

- Riociguat

A. Pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA)

Discussion:

Exertional dyspnea with an elevated JVP, loud P2, left parasternal heave, S4 gallop and clear lung auscultation suggest RV failure. History of a prior leg swelling raised suspicion for venous thromboembolism (VTE). CTPA confirmed a large central clot with recanalization (Images 1 a, b) and echocardiography showed severely elevated PA pressures. Group II, III and V pulmonary hypertension (PH) were ruled-out and a diagnosis of group IV PH, or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), was made. Oral anticoagulation and diuretics were started. The patient underwent emergent PEA.

Image 1a & b. CTPA showing central/proximal arterial occlusion (orange), partial recanalization of blood-flow (yellow) & contrast-reflux in hepatic sinusoids consistent with high right-sided venous pressures (pulmonary hypertension) (blue).

CTEPH is a rare complication of VTE (incidence: 0.4-6.2%)1 and typically manifests within 2 years after an event. Prior VTE is not apparent in approximately 25% of patients. Left untreated, CTEPH is progressive with median survival of 10-20% at 2-3 years.2

Large clot-burden and/or recurrent thromboemboli may overwhelm lytic capacity, preventing complete dissolution. Inadequate intensity and/or duration of anticoagulation, delayed diagnosis or a persistent prothrombotic state 2 maintain a milieu for clot propagation, which increases risk for complications such as chronic thromboembolic disease (CTED) or CTEPH.3,4 CTED is abnormally organized residual thromboemboli containing inflammatory cells forming a highly adherent clot within vessels (Image 2). Although persistent proximal vessel thrombi are a major inciter, subsequent small-vessel vasculopathy plays a significant role in disease progression. Redistribution of blood flow to non-occluded pulmonary arteries and large pulmonary-systemic anastomoses expose vessels to higher blood flow and shear-stress, endothelial dysfunction and increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Small-vessel vasculopathy ensues with development of resting PH, or CTEPH.4

Diagnostic criteria include right-heart catheterization derived resting mean PA pressure (mPAP) ≥20 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≤15 mmHg and PVR ≥3 Wood units (precapillary PH) with persistent angiographic pulmonary arterial thrombotic obstruction despite ≥3 months of effective anticoagulation.1 Pulmonary angiogram findings include PA dilatation, hypertrophied bronchial arterial collaterals, ring-like stenosis, webs/slits, pouches, wall irregularities, and complete vascular obstructions.

Curative treatment is possible, necessitating prompt and accurate diagnosis. Patients with prior VTE with persistent dyspnea or exercise-limitation despite appropriate anticoagulation should undergo screening. Overt RV failure is a late presentation. Ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan remains first-line screening test and helps distinguish CTEPH from pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). A normal scan rules out CTEPH (sensitivity 90-100%). VQ scan has a higher sensitivity than CTPA (97.4% vs 51%).1 Still, CTPA is often performed before surgery to determine proximal clot extension.

All patients should undergo assessment for curative PEA – the first-line treatment option for operable CTEPH. In-hospital mortality following PEA is <5% and related to surgical experience and baseline preoperative PVR.5 Survival rate past the 3-month perioperative phase exceeds 90% at 5-years.5 Our patient underwent successful PEA and discharged home on room air on hospital day 9. Image 2 shows extracted main PA clots.

Diuretics, oxygen, spironolactone and lifelong anticoagulation are general supportive therapies for patients with CTEPH and cor pulmonale. Thrombolysis is not used for chronic pulmonary emboli. Riociguat, an oral soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator, is approved for medical management of inoperable or persistent/recurrent CTEPH. Options B, C, D and E are incorrect.

Image 2. Highly adherent clot retrieved from main pulmonary arteries (pulmonary endarterectomy).

References

-

Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jais X, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1).

-

Mehta S, Helmersen D, Provencher S, et al. Diagnostic evaluation and management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J. 2010;17(6):301-334.

-

Nijkeuter M, Hovens MM, Davidson BL, Huisman MV. Resolution of thromboemboli in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Chest. 2006;129(1):192-197.

-

Simonneau G, Torbicki A, Dorfmüller P, Kim N. The pathophysiology of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(143).

-

Jenkins D. Pulmonary endarterectomy: the potentially curative treatment for patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24(136):263-271.