Going Crazy

Secondary Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis

Mordechai Pollak 1, Rayfel Schneider 3, Tom Kovesi 4, Johannes Roth 5, Elizabeth Nizalik 6, Melinda Solomon 1 and Felix Ratjen 1,2

1Division of Respiratory Medicine, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Translational Medicine, Sickkids Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Division of Rheumatology, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Division of Respiratory Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Canada. 5Division of Rheumatology, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Canada. 6Division of Pathology, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Canada

Case

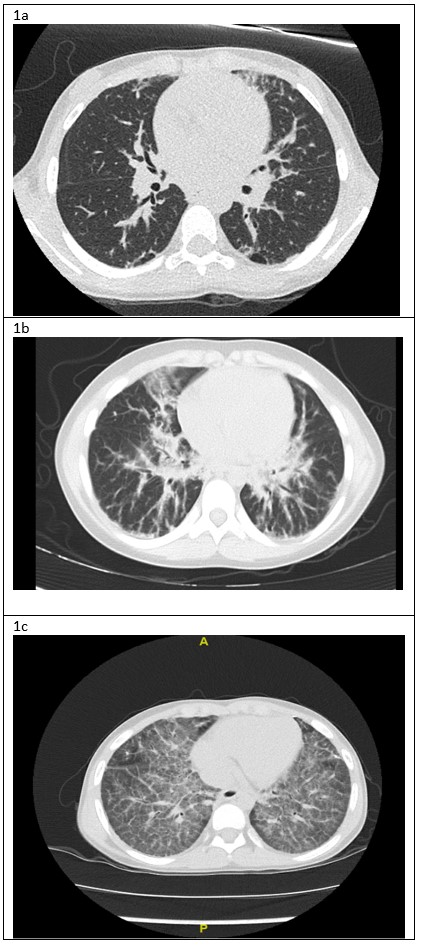

A 3-year-old female initially presented with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and macrophage activation syndrome, refractory to many biological agents. At age seven she developed exercise intolerance, chronic cough, nocturnal hypoxemia and marked digital clubbing. Along with her underlying disease that was poorly controlled, her respiratory symptoms gradually worsened. At the age of 9, she was under the 5 th percentile for weight. Her physical examination was notable for mild tachypnea, increased work of breathing, and mildly decreased air entry bilaterally with fine crackles throughout. She had significant exercise intolerance and required supplementary oxygen for sleep and all activities. Her chest CT scans from ages 7, 8 and 9 years can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1: A) Chest CT lung window, age 7: Bilateral sub-pleural blebs and scattered reticular markings. B) Chest CT lung window, age 8: Interstitial infiltrates bilaterally, more prominent in the peri-hilar region. C) Chest CT lung window, age 9: bilateral diffuse “crazy paving” pattern

Question

What is the appropriate treatment for her disease?

- Inhalations of nebulized recombinant GM-CSF

- Whole lung lavage

- Antibiotics

- Control of the rheumatologic disease

- Chloroquine

D. Control of the rheumatologic disease

Incorrect answer explanation:

A - Inhalation of nebulized recombinant GM-CSF is a treatment for primary PAP and not for secondary PAP.

B - While whole lung lavage is considered first line treatment for primary PAP, it is not as successful for secondary PAP.

C - The gradual worsening of symptoms and imaging with no acute decline makes a bacterial etiology less likely.

E - Chloroquine is not considered a treatment for secondary PAP.

Discussion

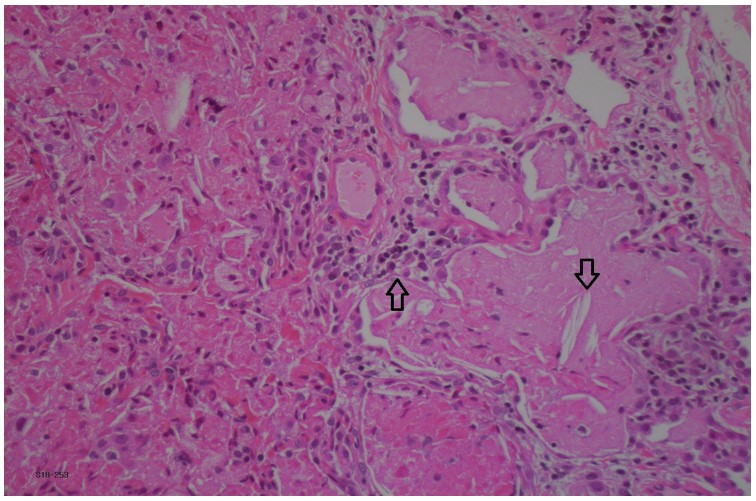

This patient was diagnosed with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) at 3 years of age. Unfortunately, her rheumatologic disease was poorly controlled despite multiple medications including systemic corticosteroids (oral and IV pulse), Anakinra, Canakinumab, Tocilizumab, Tofacitinib, Cyclosporine, Sirolimus and Emapalumab. Four years after her initial presentation she developed respiratory symptoms, which worsened over the next two years. As can be seen in figure 1a, her initial chest CT was nonspecific. A lung biopsy was performed at age 8 years which showed pulmonary alveolar lipoproteinosis with minimal interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and no fibrosis (Figure 2). Following these pathological results, she was tested for anti- granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) antibodies and for genetic mutations causing pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and was found to be negative. Whole exome sequencing found a mutation of unknown significance in NLC4 gene (c. 1174_1176delCAC), a gene that is associated with auto-inflammatory disease and MAS 1. She continued to deteriorate clinically and her most recent CT scan (figure 1c) showed a classic pattern of “crazy paving” in keeping with the diagnosis of secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis 2. A bronchoscopy and segmental lung lavage with 10/ml kg body weight was carried out, however despite excellent BAL return (>80% of instilled volume) the BAL fluid did not appear “milky” and it was not possible to mobilize significant amounts of proteinaceous material.

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) is a condition that is associated with excessive accumulation of surfactant lipoprotein in the alveolar space and results in defective air exchange and hypoxemia. Generally, PAP can be divided into primary and secondary disease. Primary PAP can be caused by autoimmune antibodies to GM-CSF or rarely, genetic defects in the GM-CSF receptor that block signaling to alveolar macrophages and impair their ability to clear surfactant. The secondary form is less understood and can be seen in several categories of disorders such as infections, exposure to inhaled chemicals, hematologic malignancies, immune deficiencies and rheumatologic disorders.

While both forms of PAP are similar in symptom presentation and imaging findings such as the classical “crazy paving” image in CT 2, the treatments are different. Removing the excessive proteinaceous material from the alveoli by whole lung lavage is the mainstay of treatment for primary PAP 3, this procedure has been reported to be less successful for treatment of secondary PAP 4. Similarly, for patients with Primary (autoimmune) PAP, it has been shown recently in a randomized controlled trial that daily inhaled recombinant GM-CSF is superior to placebo in improving pulmonary gas transfer and functional health status, with similar rates of adverse events 5. No such established therapies are available for secondary PAP. Due to the severity of our patient’s disease and lack of effective therapies, a double lung transplant was considered. However, there is limited evidence about transplantation success rates in such scenarios and her SoJIA/MAS was still poorly controlled, so it was decided to proceed with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a final attempt to control the underlying disease before reconsidering lung transplantation.

In conclusion, the treatment for secondary PAP should focus on treatment of the underlying cause. Pulmonary disease is increasingly evident in children with SoJIA 6 and awareness of this clinical entity and its associated complications is important.

Figure 2: Lung biopsy pathology with pulmonary alveoli filled with eosinophilic exudate containing macrophages and cholesterol clefts (downward arrow). Mild interstitial lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (upward arrow). Hematoxylin-phloxine–saffron stain, x20.

References

-

Romberg N, Vogel TP, Canna SW. NLRC4 inflammasomopathies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17(6):398-404. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000396

-

Wang BM, Stern EJ, Schmidt RA, Pierson DJ. Diagnosing Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. Chest. 1997;111(2):460-466. doi:10.1378/chest.111.2.460

-

Zhao Y-Y, Huang H, Liu Y-Z, Song X-Y, Li S, Xu Z-J. Whole Lung Lavage Treatment of Chinese Patients with Autoimmune Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis: A Retrospective Long-term Follow-up Study. Chin Med J. 2015;128(20):2714-2719. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.167295

-

Chaulagain CP, Pilichowska M, Brinckerhoff L, Tabba M, Erban JK. Secondary pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in hematologic malignancies. Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy. 2014;7(4):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.hemonc.2014.09.003

-

Trapnell BC, Inoue Y, Bonella F, et al. Inhaled Molgramostim Therapy in Autoimmune Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(17):1635-1644. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1913590

-

Schulert GS, Yasin S, Carey B, et al. Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Lung Disease: Characterization and Risk Factors. Arthritis & Rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ). 2019;71(11):1943-1954. doi:10.1002/art.41073