All That is Hazy is not Pneumonia

Case:

An 80-year-old woman with a medical history of congestive heart failure (HFrEF), hypertension, and squamous cell carcinoma of the right middle lobe diagnosed three months ago presented with new-onset shortness of breath and non-productive cough for the last week, which progressively worsened. Since her diagnosis, the patient had received two cycles of radiation therapy, with the last radiation completed about two weeks ago. She denied any fever or chills.

Physical exam: The patient was afebrile, oxygen saturation ranging 89 to 94% on room air, no lower extremity edema or calf muscle tenderness, minimal lung crackles heard mostly over the right side.

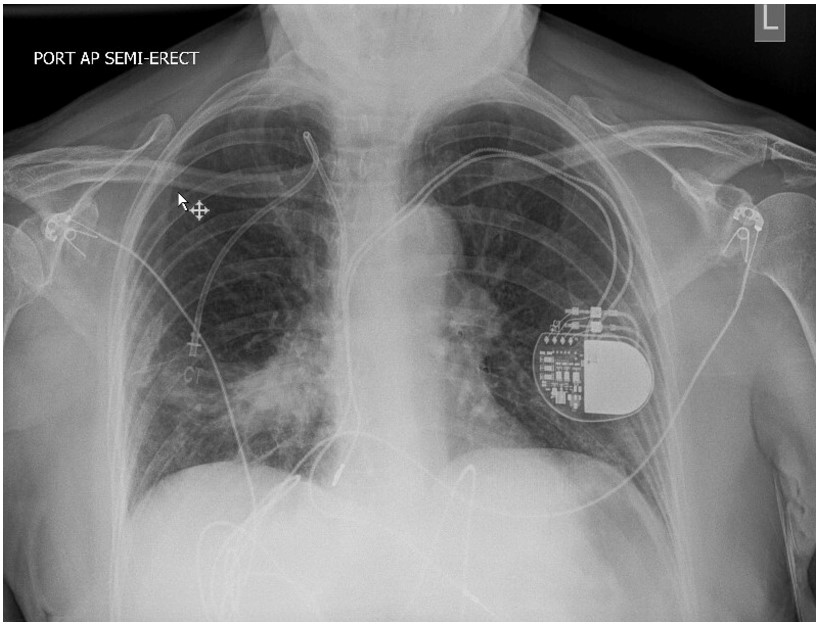

An arterial blood gas obtained at the time of presentation showed a pH of 7.5 with PaO2 of 75 mmHg and PaCO2 of 25.4 mmHg. White cell count was normal at 7,700. A chest X-ray obtained is below.

Question:

What is the diagnosis? How would you treat the condition?

- Community-acquired pneumonia; antibiotics

- Radiation pneumonitis; corticosteroids

- Atelectasis; incentive spirometry

- Radiation pneumonitis; observation

B. Radiation pneumonitis; corticosteroids

Discussion:

The patient was diagnosed with radiation pneumonitis (radiation-induced lung injury). She was treated with four weeks of oral prednisolone, and complete recovery was achieved. The absence of fever and white cell count elevation makes an infectious etiology like community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) less likely here (although low-grade fever and mild leukocytosis with left shift can frequently be associated with radiation pneumonitis, making it difficult to differentiate from CAP). Although right middle lobe atelectasis can give a similar X-ray picture, her history and absence of signs of volume loss make it less likely; a CT or lateral view X-ray could be obtained to confirm.

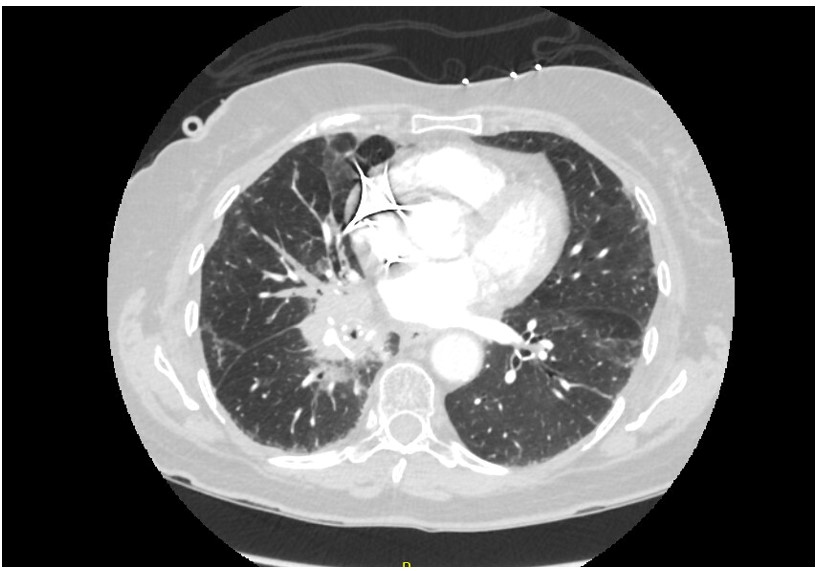

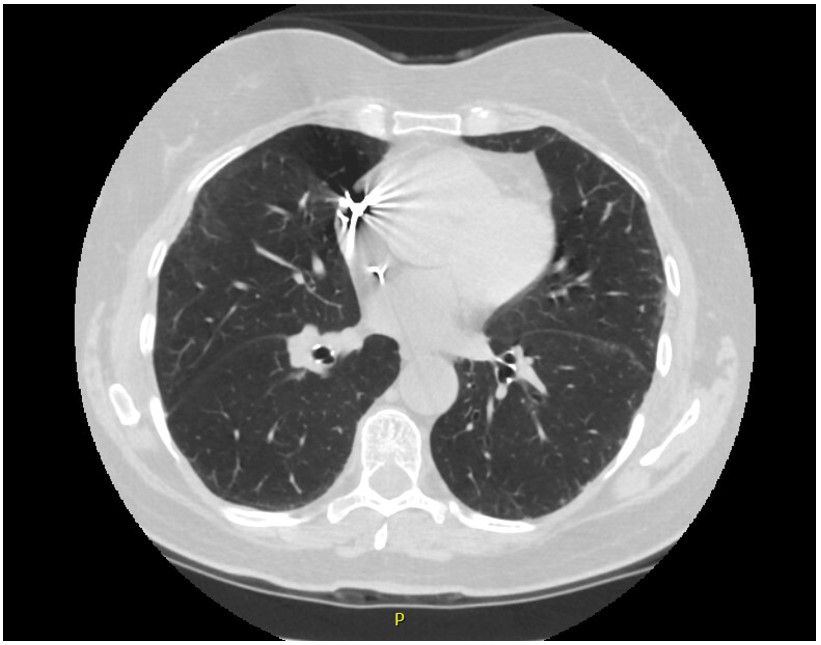

Other important differentials to consider are pulmonary embolism, exacerbation of underlying heart failure, spread of malignancy, or chemotherapy/immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced pneumonitis. A CT scan with contrast was done mainly to exclude pulmonary embolism and atelectasis, which helped confirm the diagnosis (Image 1). Compared to the CT scan one month ago (Image 2), areas of consolidation surrounding the lung mass can be seen in the current CT. The respiratory culture obtained at admission grew normal respiratory flora, and the blood culture remained sterile after five days since admission.

Radiation-induced lung injury is divided into radiation fibrosis and radiation pneumonitis. Radiation fibrosis develops months to years after radiation therapy, while pneumonitis is seen within weeks to a few months in patients who received radiation. Up to 5-10% of patients who received radiation develop some degree of radiation pneumonitis.1 The incidence varies with the type and dose of radiation used2; 3D radiation therapy has more risk compared to intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRD), and photon therapy possesses more risk for surrounding normal lung tissue damage compared to proton therapy.3,4 Other risk factors associated with the development of radiation-induced lung injury are concurrent chemotherapy, older age, disease location in the mid or lower lung, COPD, interstitial lung disease, and genetic factors.5 Patients usually present with non-productive cough, new-onset or worsening dyspnea, low-grade fever, or pleuritic chest pain. Associated pleural effusion or dermatitis can be seen in some cases. Diagnosis is mostly clinical with a temporal relationship to radiation and exclusion of other conditions. Elevated LDH and CRP are non-specific laboratory findings seen in most patients. Imaging will classically show perivascular haziness and patchy opacities, which may be limited to the areas of radiation rather than to an anatomical division. In the fibrotic phase, PFT will show findings of restrictive lung disease. There are no clear guidelines for treating this condition, but supportive care is often enough if symptoms are mild. For more severe symptoms and sub-acute presentation, oral glucocorticoids for 2 to 4 weeks with a gradual taper are recommended by most authorities.4 In most patients, radiation pneumonitis completely resolves but can rarely progress to lung fibrosis.

References

-

Abratt RP, Morgan GW. Lung toxicity following chest irradiation in patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;35(2):103-109. doi:10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00334-8

-

Graham MV, Purdy JA, Emami B, et al. Clinical dose-volume histogram analysis for pneumonitis after 3D treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45(2):323-329. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00183-2

-

Kobayashi H, Uno T, Isobe K, et al. Radiation pneumonitis following twice-daily radiotherapy with concurrent carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(5):464-469. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyp190

-

Jain V, Berman, AT. (2018). Radiation Pneumonitis: Old Problem, New Tricks. Cancers, 10(7), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10070222

-

Vogelius IR, Bentzen SM. A literature-based meta-analysis of clinical risk factors for development of radiation induced pneumonitis. Acta Oncol. 2012 Nov;51(8):975-83. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.718093. Epub 2012 Sep 5. PMID: 22950387; PMCID: PMC3557496.