Air, Air Everywhere

- Akesh Thomas, MBBS, Department of Internal Medicine, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN

- Dennis Peter Jacob, MBBS, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Mary Mercy Livonia Hospital, Livonia, MI

- Girendra V Hoskere, MBBS, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN

Case

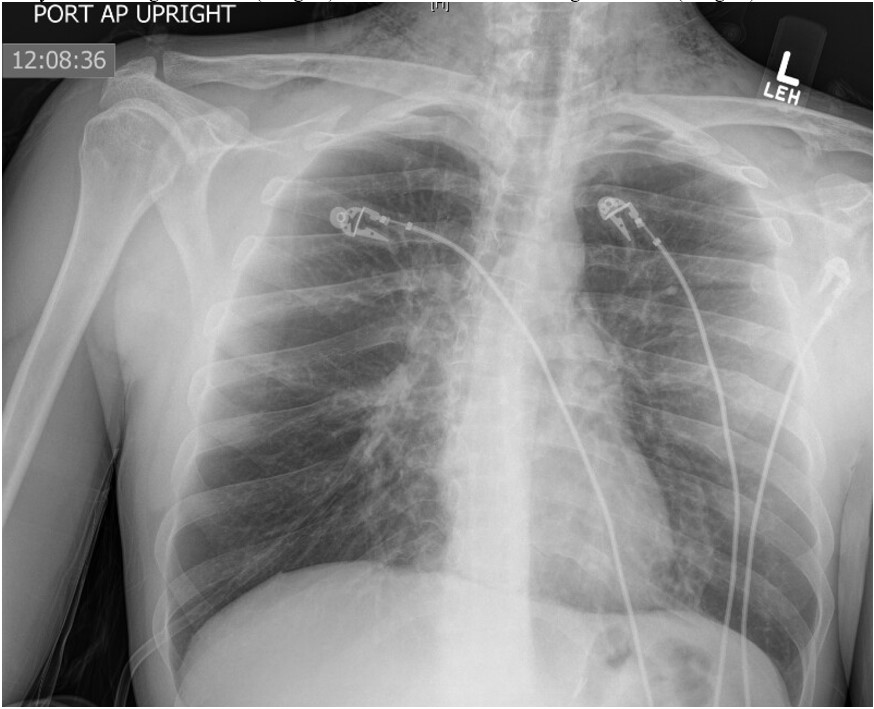

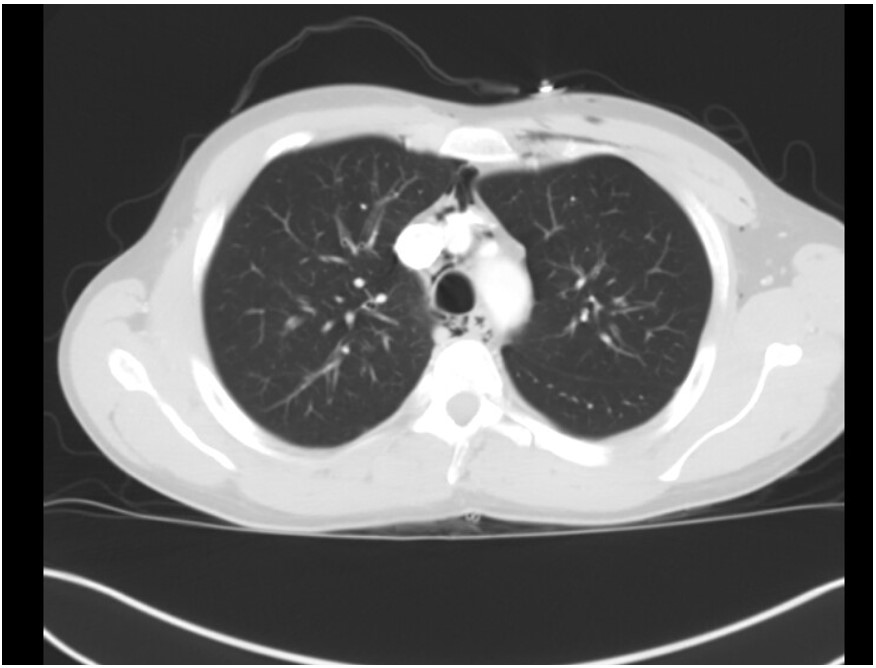

A 28-year-old Caucasian male with a history of asthma and polysubstance abuse came with complaints of shortness of breath and cough for two weeks, which worsened over the last 24 hours. At the time of presentation, he was saturating 88-90% on room and 94% with 2 liters of oxygen. He was able to speak in full sentences and was not using any accessory muscles of respiration to breathe. Physical exam was significant for a respiratory rate of 24, bilateral expiratory wheezes, and palpable crepitus of the left upper chest wall and shoulder regions. Arterial blood gas showed a pH of 7.44 with PaO 2 of 77 and PaCO 2 of 34. Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within the normal range. The chest X-ray obtained is given below (Image 1). A CT scan obtained is also given below (Image 2).

Image 1

Image 1

Image 2

Question

How would you manage this patient?

- Immediate Bronchoscopy

- No Treatment Needed

- Inhaled Beta-agonists and Oral/IV steroids

- Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation

- Emergency Barium Esophagogram

C. Inhaled Beta-agonists and Oral/IV steroids

Discussion

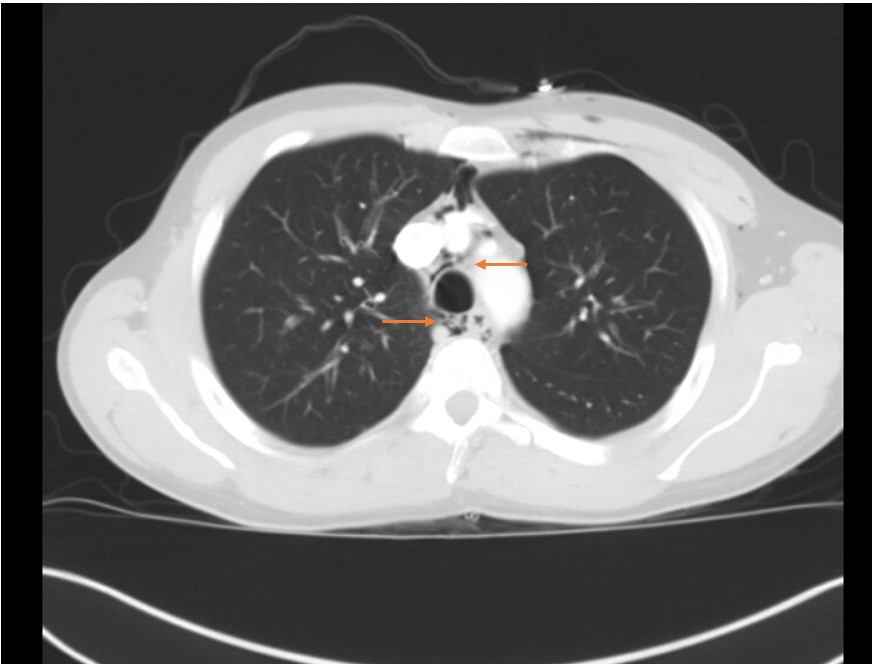

The patient has spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) and associated sub-cutaneous emphysema, an uncommon complication of asthma exacerbation [1]. The chest X-ray shows subcutaneous emphysema, mostly in the neck and upper chest area. The CT image shows areas of visible mediastinal air [Image 3]. SPM is believed to occur due to rupture of marginal alveoli from increased intra-alveolar pressure [2]. Over distention of the alveoli and decreased perivascular interstitial pressure can also be contributing to the alveolar rupture. Asthma and inhalational drug abuse are the two common causes of SPM. Other rare causes include coughing, shouting, strenuous exercise, and scuba diving [3]. Hamman's sign (crunching noise heard with heartbeat on auscultation) is a classic finding in pneumomediastinum. A chest x-ray in the appropriate clinical setting is often diagnostic; typical findings include gas lining lateral to main pulmonary artery and aorta, continuous left hemidiaphragm sign, Naclerio's V sign, and ring around the artery sign [4]. If in doubt, a CT scan of the chest is warranted to exclude any major viscous perforation. SPM is self-resolving with supportive management, including oxygen supplementation and treatment of the underlying cause. Here the appropriate treatment for asthma exacerbation is needed, which is inhaled beta-agonist and steroid treatment (choice C is correct, and B is incorrect). Surgical intervention may become necessary in very rare cases with cardio-respiratory compromise [5], as in patients with tension pneumomediastinum. It is noteworthy that in many cases, if the patient is asymptomatic, observation without any active intervention is adequate.

Bronchoscopy would be an unnecessary and unyielding intervention for this patient (choice A is incorrect). The severity of the asthma exacerbation does not require intubation and mechanical ventilation (choice D is incorrect) but should be treated with inhaled medications and steroids. Esophagogram can be done in cases of SPM if the suspicion of esophageal perforation is high. In this case, the concern for perforation is low with the history provided. If performed, it should be done with a water-soluble contrast like gastrografin rather than barium (choice E is incorrect).

Image 3

References

-

Akinyemi, R., Ogah, O., Akisanya, C., Timeyin, A., Akande, K., Durodola, A., Ogundipe, R., & Osinfade, J. (2007). Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema complicating acute exacerbation of bronchial asthma. Annals of Ibadan postgraduate medicine, 5(2), 78–79. https://doi.org/10.4314/aipm.v5i2.64035

-

Faruqi S, Varma R, Greenstone MA, Kastelik JA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a rare complication of bronchial asthma. J Asthma. 2009 Nov;46(9):969-71. doi: 10.3109/02770900903215635. PMID: 19905929.

-

Mitchell, P., King, T., & O'Shea, D. (2015). Subcutaneous Emphysema in Acute Asthma: A Cause for Concern?. Respiratory Care, 60(8), e141-e143. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03750

-

Bejvan, S., & Godwin, J. (1996). Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs. American Journal Of Roentgenology, 166(5), 1041-1048. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.5.8615238

-

Unger, D., & Pifarré, R. (1972). Tracheotomy for Subcutaneous Emphysema and Pneumomediastinum Complicating Asthma. Chest, 61(7), 691-692. doi: 10.1378/chest.61.7.691