A Batty Non-resolving Lung Abnormality

Xiao Wang, MD, Diagnostic Radiology Resident, University of Minnesota

Kexin Zheng, Swenson College of Science and Engineering, University of Minnesota, Duluth

Tadashi Allen, MD, Assistant Professor of Radiology, University of Minnesota

Case

A 21-year-old female with no significant past medical history presents with fever, dry cough and intermittent chest pain for 1 month. She is a college sophomore majoring in animal science. The patient was taking mammology and ornithology field classes and was bit by squirrel and exposed to ticks, but it seemed of little consequence. She did reported catching and handling bats in summer. She is a nonsmoker and denies any drug use. She has no exposure to tuberculosis, but volunteers in a homeless shelter.

Vital signs are: T 38.2 °C, BP 116/69, HR 119, RR 16, SpO2: 98 % on air. No respiratory distress. Normal breath sounds without wheezes or rales. WBC is 7,300 with unremarkable differential. The basic metabolic panel and liver function testing are all within normal limits. Tests for influenza, strep and HIV are all negative. A quantiferon gold test was also negative.

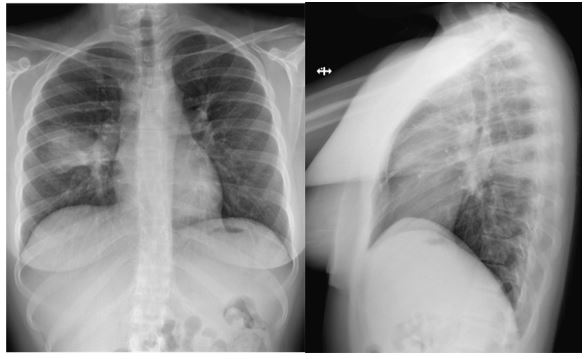

Images 1 & 2 - PA and lateral radiographs of the chest at time of presentation are shown.

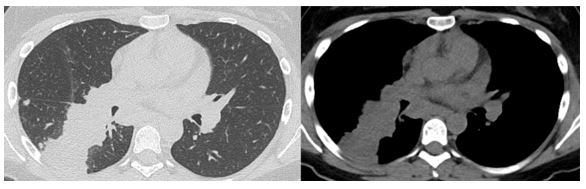

Images 3-4 - Representative slices from the subsequent noncontrast chest CT are displayed.

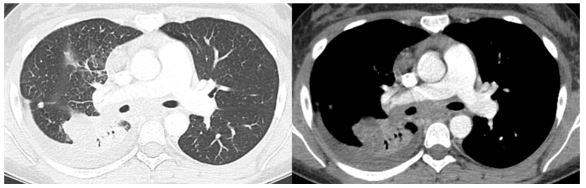

Images 5-6 - Follow up enhanced chest CT obtained 10 months after initial CT scans are shown.

Question

What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Tuberculosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Klebsiella Pneumonia

- Pneumocystis Pneumonia

- Neoplasm

B. Histoplasmosis

Discussion

Chest radiographs demonstrate patchy air space opacities and consolidation in the superior segment of the right lower lobe. Concurrent chest CT shows segmental/sub-segmental consolidation in the superior segment of the right lower lobe with scattered satellite peripheral nodules and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. There is no pleural effusion. The radiologic presentation is not specific and the differential diagnoses include infections (viral, bacterial, or fungal), pulmonary edema, hemorrhage, chronic interstitial lung disease such as organizing and/or eosinophilic organizing pneumonia, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, medication toxicity, and neoplasms.

Patient’s clinical presentation of fever and cough is typical for infection, particularly in a very young adult. Pneumocystis pneumonia (Option D) seems unlikely given patient’s negative past medical history and immune-competent status. Klebsiella Pneumonia (Option C) tends to be in higher prevalence in older patients with alcoholism and debilitated hospitalized patients. Typical radiographic findings include cavitary lesion with a bulging fissure sign, which is not present in the current case. The dense consolidation, satellite nodules and mediastinal lymph nodes demonstrated in this case are characteristics of granulomatous disease, such as mycobacterial or fungal infections. Tuberculosis is excluded given negative Quantiferon Gold test (Option A). Patient was an animal science major and admitted to handling bats recently. Patient was subsequently found to be positive for serum and urine histoplasma antigen which eventually lead to the diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis (Option B)1. Other less common bat-related infections such as Ebola or Hantavirus were considered but no microbiologic evidence was found.

Histoplasmosis is a common endemic and systemic fungal infection in the North America2,3. Some populations studies have shown that over 80% of young adults from endemic regions of North America have been previously infected by Histoplasma capsulatum. In acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, majority of cases have no symptoms2,3. Most common symptoms reported include fever, cough, dyspnea, chest pain, malaise, headache, myalgia, dysphagia and abdominal pain. Emphysematous changes, mediastinal granuloma, fibrosing mediastinitis and broncholithasis are late stage manifestations. In immunocompetent individuals, histoplasmosis infection is usually self-limited and no treatment is required2,3,4. Antifungal medications such as Itraconazole, Ketoconazole and amphotericin B are treatment options. For mediastinal histoplasmosis complicated by fibrosing mediastinitis, drug treatment is usually not effective and surgery is often dangerous and unsuccessful. Vascular and airway stents can be considered for treatment of stenosis secondary to fibrosing mediastinitis5.

In our patient, persistent respiratory symptoms, positive microbiology lab test and pulmonary consolidation of the imaging study drove us to decide to initiate treatment. The patient underwent treatment with itraconazole for one month (200mg bid, initial 3 days tid) with significant improvement in her symptoms. She was then off of the itraconazole for 3 weeks but her symptoms including worsening cough, fever returned. Additional extensive work up for alternative diagnoses was performed. Repeat Quantiferon Gold test remains negative. The patient also had flexible bronchoscopy with EBUS lymph node biopsies. BAL cytopathology was negative but histopathology on two of three EBUS lymph node biopsies showed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and with a background polymorphous lymphoid cell population. There was no evidence for malignant cells (Option E). Four fungal cultures (and three acid-fast bacteria cultures, as well as Nocardia and Actinomyces BAL cultures) were all without growth. The patient subsequently resumed itraconazole again with improved symptoms. Unfortunately, there were waxing and waning symptoms during the following few months with 2 short hospitalizations. Follow up CT scan (Images 5-6) obtained 10 months after the initial scans demonstrate continued consolidation and cicatricial atelectasis of the superior segment of the right lower lobe with small amount of pleural effusion. There are enlarged anterior mediastinal and subcarinal lymph nodes with stippled early calcification encasing right pulmonary artery with borderline dilated main pulmonary artery (diameter greater than same level aorta), but not at a magnitude to be suspicious for fibrosing mediastinitis at this time. After recheck of patient’s immunostasis and microbiology lab test, decisions were made to start voriconazole 300 mg BID with continued aggressive treatment of pulmonary histoplasmosis.

References

-

Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a Clinical and Laboratory Update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(1):115-132.

-

Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30(2):217-225.

-

Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Histoplasmosis: 2007 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

-

Rubin SA, Winer-Muram HT. Thoracic histoplasmosis. J Thorac Imaging. 1992;7(4):39-50.

-

Albers EL, Pugh ME, Hill KD, Wang L, Loyd JE, Doyle TP. Percutaneous vascular stent implantation as treatment for central vascular obstruction due to fibrosing mediastinitis. Circulation. 2011;123(13):1391-1399.