Reviewed By Pulmonary Circulation Assembly

Submitted by

Stephen C. Mathai

Fellow, Division of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine

Department of Medicine

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Rubin Tuder

Professor, Division of Cardiopulmonary Pathology

Department of Pathology

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Paul M. Hassoun

Associate Professor, Division of Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine

Department of Medicine

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Submit your comments to the author(s).

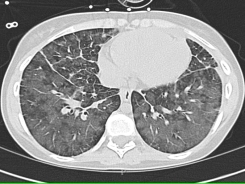

History

An 18-year-old woman presents as a transfer from an outside hospital for further evaluation and treatment for shortness of breath. She was last in her usual state of health 4 years ago when she noted slowly progressive shortness of breath, initially noted while playing soccer. She was evaluated by her primary care physician who performed pulmonary function tests and treated her with bronchodilators for presumed asthma. Her symptoms stabilized, but she noted worsening of shortness of breath to the point where she could not walk farther than 50 feet on flat ground along with new onset of lower extremity edema 2 months prior to presentation at our institution. Further, she complained of symptoms suggestive of Raynaud’s phenomenon. The patient was subsequently referred for a computed tomography of the chest (Figure 1) and ultimately underwent a video-assisted thorascocopic surgery with biopsy (Figures 2 and 3). After the surgery, the patient experienced prolonged hypoxemia, prompting an echocardiogram that revealed substantial elevation of the estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (90 mmHg), dilated right ventricle and dilated right atrium. Right heart catheterization was performed and revealed a mean right atrial pressure of 18 mmHg, mean pulmonary artery pressure of 59 mmHg, cardiac index of 3.2 L/min/m2, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 13 mmHg. Based upon these values, the patient was started on intravenous epoprostenol. A few days after initiation of epoprostenol, the patient developed worsening shortness of breath. She was subsequently transferred to our institution for further evaluation and treatment.

Past Medical History

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, resolved

Presumed asthma

Vaccination up to date

Physical Exam

Lab

Hemoglobin 8.0 mg/dL (baseline 12.0 mg/dL)

Serum creatinine normal

No hematuria or casts in urine

Antinuclear antibody positive 1:320

Anticentromere antibody positive

All other vasculitis serologies negative

The patient was started on therapy and subsequently improved. She was weaned off supplemental oxygen by the time of discharge.

Figures

Figure 1: Chest CT. On parenchymal windows, the CT of the chest demonstrates diffuse bilateral patchy infiltrates in an alveolar pattern, as well as interlobular septal thickening. There is no pleural effusion noted.

Figure 2: Pathology. Interlobular septal vein showing complete occlusion (arrow). Note the partial occlusion in the branch extending into alveolated tissue (short arrow) outlined by the Movat stain.

Figure 3: Pathology. Large pulmonary vein showing complete luminal obliteration by loose connective tissue, highlighted by a MOVAT stain that outlines the medial elastic tissue.

References

- Rubin LJ. Primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 1997;336:111-7

- Rosenthal A, Vawter G, Wagenvoort CA. Intrapulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Am J Cardiol 1973;31:78-83

- Swensen SJ, Tashjian JH, Myers JL, et al. Pulmonary venoocclusive disease: CT findings in eight patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;167:937-40

- Palmer SM, Robinson LJ, Wang A, et al. Massive pulmonary edema and death after prostacyclin infusion in a patient with pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Chest 1998;113:237-40

- Bailey CL, Channick RN, Auger WR, et al. "High probability" perfusion lung scans in pulmonary venoocclusive disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1974-8

- Pietra GG, Edwards WD, Kay JM, et al. Histopathology of primary pulmonary hypertension. A qualitative and quantitative study of pulmonary blood vessels from 58 patients in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Registry. Circulation 1989;80:1198-206

- Dorfmuller P, Humbert M, Perros F, et al. Fibrous remodeling of the pulmonary venous system in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue diseases. Hum Pathol 2007;38:893-902

- Ghofrani HA, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Imatinib for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1412-3

- Rabiller A, Jais X, Hamid A, et al. Occult alveolar haemorrhage in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 2006;27:108-13