Reviewed By Clinical Problems Assembly

Submitted by

Camilla K. B. Matthews, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Pediatrics

Wisconsin Sleep Center, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

Madison, Wisconsin

Mihaela Teodorescu, MD, MS

Assistant Professor

Department of Medicine

Wisconsin Sleep Center, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

Madison, Wisconsin

Submit your comments to the author(s).

History

Physical Exam

On exam, the patient had a blood pressure of 102/84 mm Hg and pulse of 111 beats/min. Her BMI was 28 kg/m2, compared to 20 kg/m2 one year previously. Her general appearance was notable for obesity and the general facies of a child with PWS, including almond-shaped eyes, thin upper lip, and down turned corners of the mouth. HEENT exam showed no thyromegaly, however, her tonsils were 4+. Her lungs were clear to auscultation. The cardiac exam showed a regular heart rate without murmur or gallop. Musculoskeletal exam revealed subtle scoliosis. Her gait was broad based. The skin exam revealed well healed scars on the hips from osteotomies for bilateral hip dysplasia. The neurological exam was notable for diffuse hypotonia. Her skin exam was normal.

Lab

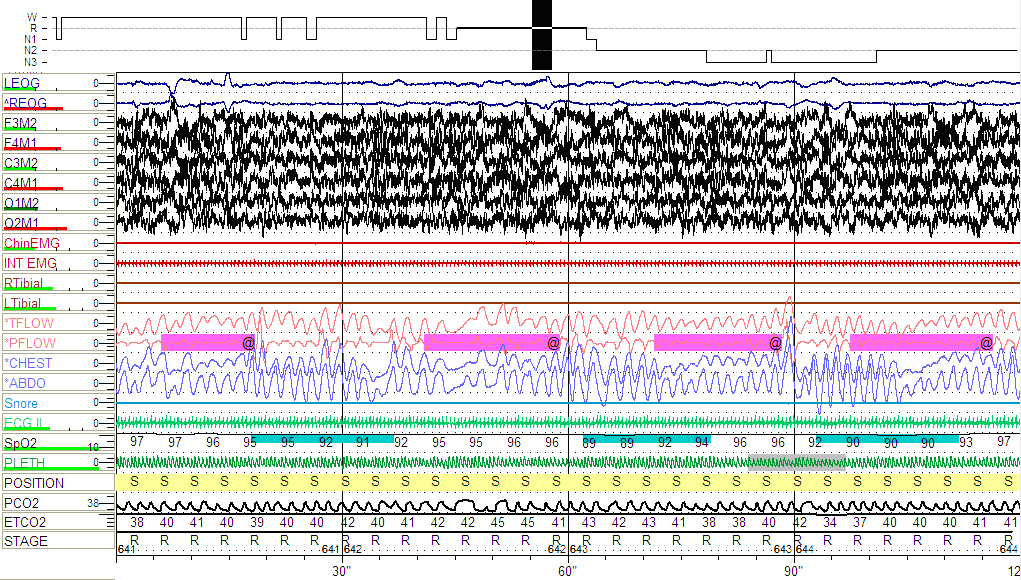

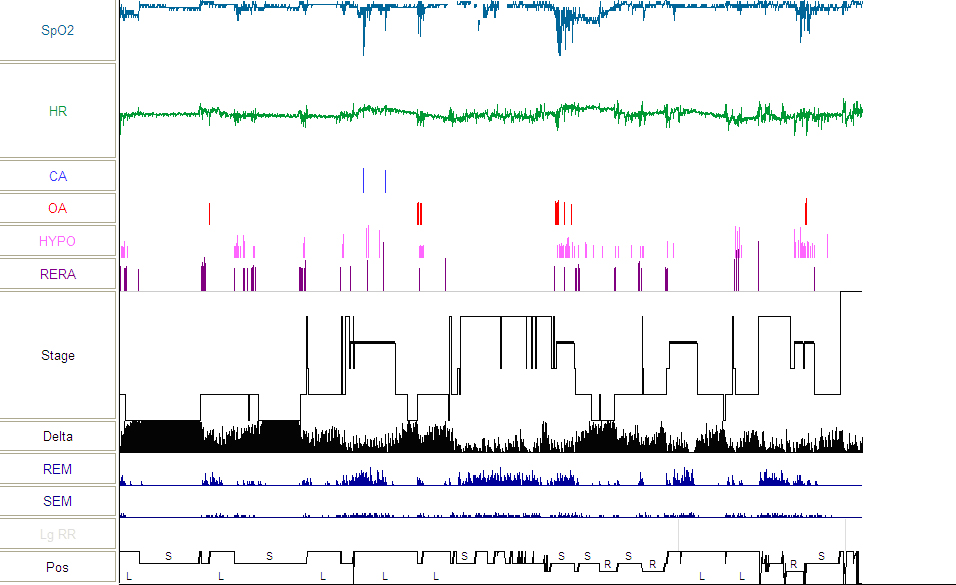

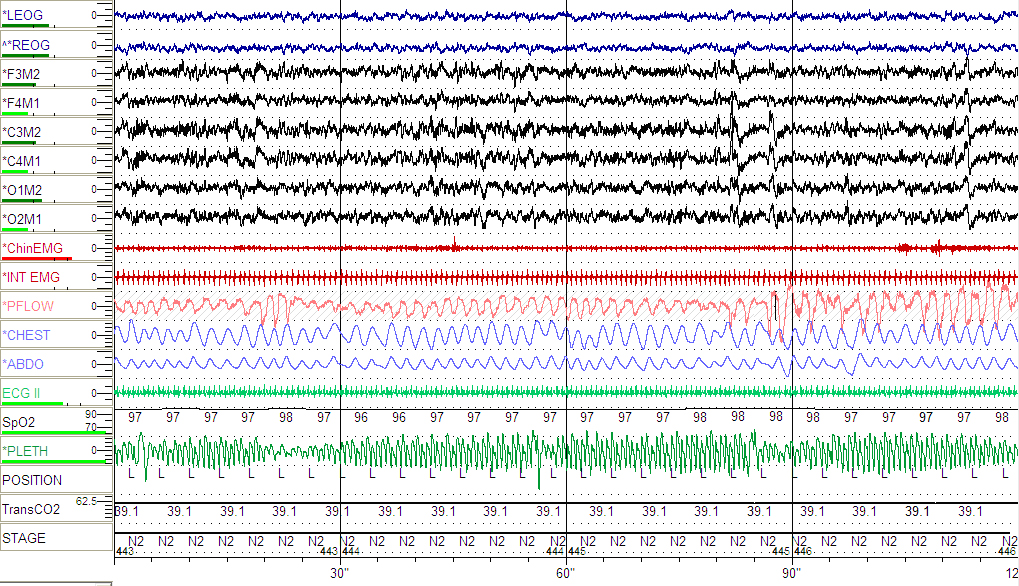

The patient was referred for a nocturnal polysomnogram (PSG). As depicted below (Fig 1), she was found to have severe OSA with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 24 events/hour and a REM sleep AHI of 38 events/hour and a lowest oxygen saturation of 81% (Fig 2).

Figures

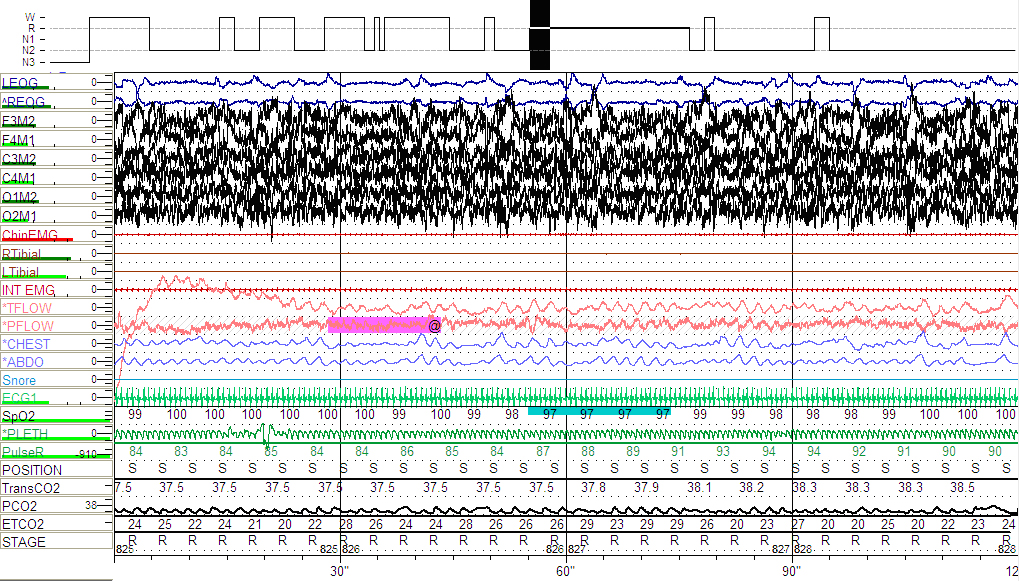

LEOG AND REOG, left and respectively right outer cantus electro-oculography electrodes; F3-M2, C3-M2 and O1-M2, left frontal, central and respectively, occipital electroencephalography electrodes; F4-M1, C4-M1 and O2-M1, right frontal, central and respectively, occipital electroencephalography electrodes; Chin EMG, submental electromyography signal; INT EMG, intercostals electromyography signal; ECG II, one standard electrocardiogram lead; RTibial and LTibial, right and respectively left lower limbs electromyography electrodes; SNORE, the snoring sound via microphone; TFLOW, the airflow via nasal/oral thermocouples; PFLOW, the airflow via nasal air pressure transducer; CHEST and ABDO, chest and respectively abdominal walls motion via inductive plethysmography; SpO2, the pulse oximetry by finger probe; PLETH, phlethysmographic waveform; POSITION, S=Supine; PCO2 and ETCO2, end tidal CO2 monitoring with accompanying waveform.

Hypnogram from baseline PSG depicting multiple respiratory events, more frequent and with lower oxygen desaturations during supine-REM sleep

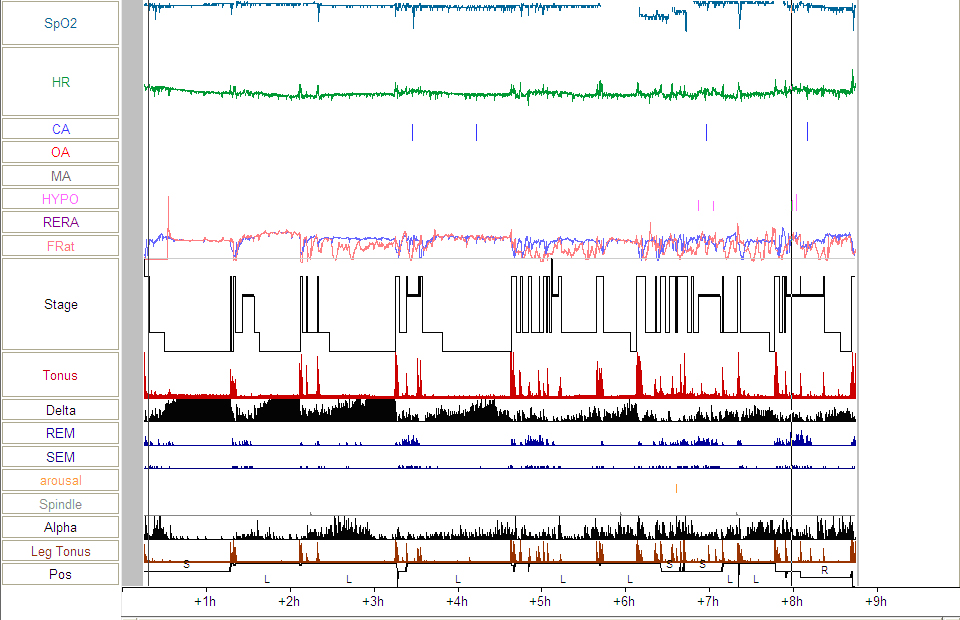

Figure 3: Hypnogram from follow-up PSG showing significant improvement in sleep-disordered breathing.

Figure 4: Follow-up PSG showing hypopnea and variability in airflow (see arrows) during supine REM sleep.

Figure 5: Follow-up PSG continued to show variability in the plethysmographic waveform (see arrows) during NREM sleep suggesting increased upper airway resistance.

References

- Nixon GM, Brouillette RT. Sleep and Breathing in Prader-Willi Syndrome. Pediatric Pulmonology 2002; 34:209-217.

- Camfferman D, McEvoy RB, O’Donoghue F, Lushington K. Prader Willi syndrome and excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2008; 12:65-75.

- Camfferman D, Lushington K, O’Donoghue F, McEvoy RB. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in Prader-Willi Syndrome: an unrecognized and untreated cause of cognitive and behavioral deficits? Neuropsychol Rev 2006; 16:123-129.

- Pavone M, Paglietti MG, Petrone A, Crino A, De Vincentiis GC, Cutrera R. Adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea in children with Prader-Willi Syndrome. Pediatric Pulmonology 2006; 41:74-79.

- Grugni G, Livieri C, Corrias A, Sartorio A, Crino A. Death during GH therapy in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: description of two new cases. J Endocrinol Invest 2005; 26(6):554-557.

- Miller JL, Shuster J, Theriaque D, Driscoll DJ, Wagner M. Sleep disordered breathing in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome during the first 6 weeks of growth hormone therapy: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009; 5(5):448-453.

- Miller J, Silverstein J, Shuster J, Driscoll D, Wagner M. Short-term effects of growth hormone on sleep abnormalities in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:413-417.

- Eiholzer U. Deaths in Children with Prader-Willi Syndrome. Horm Res 2005; 63:33-39.