Reviewed By Pulmonary Circulation Assembly

Submitted by

Jeffery Mazer, MD

Pulmonary/Critical Care Fellow

Division of Pulmonary, Sleep and Critical Care Medicine

The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Providence, RI

James R. Klinger, MD

Medical Director of the Respiratory Care Unit and Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Pulmonary, Sleep and Critical Care Medicine

Rhode Island Hospital and The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University

Providence, RI

Submit your comments to the author(s).

History

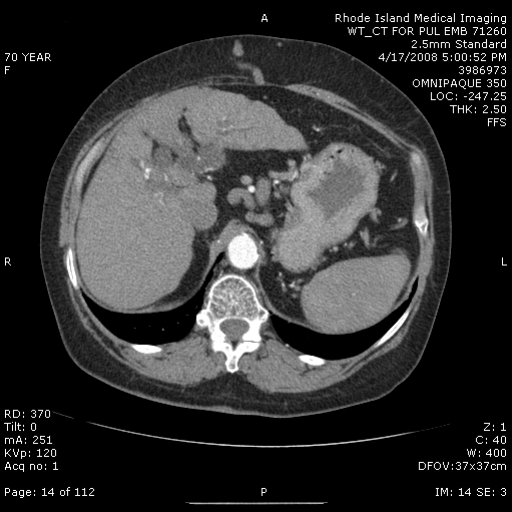

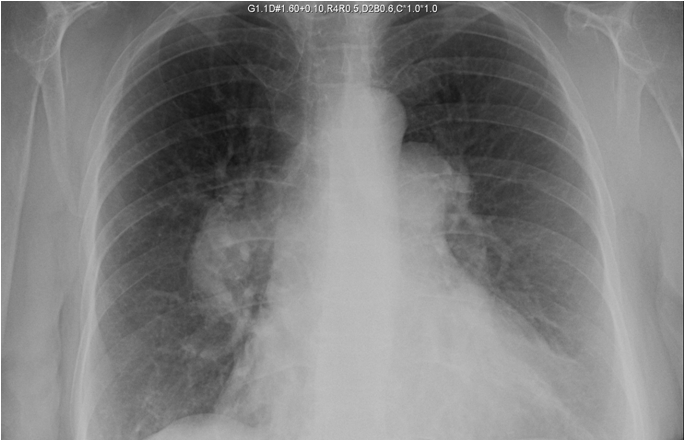

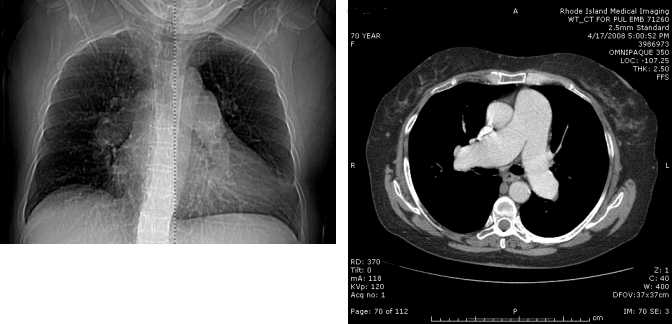

A 70-year-old woman with a history of alcoholic liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and hypothyroidism was referred for progressive dyspnea and evaluation of enlarged pulmonary arteries on chest radiograph. She had smoked approximately one pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and developed exertional dyspnea 2-3 years earlier. At that time, she was diagnosed with COPD and inhaled bronchodilators were prescribed. She continued to smoke and her dyspnea worsened. Inhaled bronchodilators had little effect. Six months earlier she had been admitted to the hospital with Clostridium difficile colitis, gastrointestinal bleeding and COPD exacerbation. During that admission, she quit smoking and was started on supplemental oxygen therapy. A chest radiograph during the hospital stay showed cardiomegaly and large bilateral pulmonary arteries (Figure 1). Upon discharge she was referred to a pulmonologist for further evaluation. A computed tomographic pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) confirmed the presence of enlarged pulmonary arteries, but no proximal filling defects were identified (Figure 2). The lung parenchyma showed mild emphysematous changes, but no large bulla. Abdominal images revealed hepatomegaly with portal and esophageal varices (Figure 3). A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) found normal cardiac chamber sizes with no evidence of valvular heart disease and normal pulmonary artery pressure.

At the time of presentation to our institution, she was comfortable at rest but reported difficulty walking more than 50 feet. She was able to ambulate in the house and perform basic housework but avoided stairs. She denied cough, sputum, wheezing, chest pain or exertional lightheadedness, but did notice some lower extremity edema.

Past Medical/Surgical History

The patient had a history of alcoholic cirrhosis but had been sober for many years. Other medical problems included hypothyroidism and peptic ulcer disease that had been treated with partial gastrectomy. She denied HIV infection, congenital heart disease, thromboembolic disease, connective tissue disease or use of anorexigens.

Medications

Synthroid, Spironolactone, Furosemide, Omeprazole, Zolpidem, Ipatroprium/Albuterol, Fluticasone

Lab

PA and lateral chest radiograph: Large dilated pulmonary arteries bilaterally, cardiomegaly, no active pulmonary disease. (Figure 1)

Laboratory tests:

INR 1.1

T. Bili 2.5

Albumin 2.6

HIV negative

ANA 1:40

Childs-Pugh Score8

Pulmonary Function Tests: FEV1 1.27 L (64% predicted), FVC 2.12 L (84% predicted), FEV1/FVC 0.60, TLC 3.87 L (90% predicted), RV 1.72 L (97% predicted), DLCO 8.24 (42% predicted) (All values slightly improved from May, 2008).

Ventilation/Perfusion Lung Scan:Heterogeneous perfusion, low probability for pulmonary embolism.

CT chest with contrast:Enlargement of the right and left main pulmonary arteries; no proximal-filling defects. No active lung disease, mild emphysematous changes without bullous emphysema. The liver is cirrhotic with evidence of esophageal and periportal varices (Figure 2).

Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE):Normal left-ventricular size and systolic function, left-ventricular ejection fraction 60-65% with impaired diastolic relaxation. Normal right-ventricular and right-atrial size. Normal right-ventricular function. Minimal tricuspid regurgitation. Right-ventricular systolic pressure 26 mm Hg assuming a right atrial pressure of 5 mm Hg. The left atrium was normal in size, normal mitral valve with physiologic mitral regurgitation, normal aortic valve with minimal calcification and trace aortic regurgitation.

Figures

Figure 1. Posterior-anterior chest radiograph showing massive enlargement of the right and left pulmonary artery.

Figure 2. CT pulmonary angiogram scout film (Left) and axial cut (Right) showing severe dilation of the pulmonary artery trunk and main right and left branches. Note the diameter of the pulmonary artery exceeds that of the aorta. No proximal filling defects are seen.

References

- Yock PG, Popp RL. Noninvasive estimation of right ventricular systolic pressure by Doppler ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation 1984; 70:657-662.

- Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Ferrari VA, Sutton MS, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, Pochettino A, Kotloff RM. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:735-740

- Edwards PD, Bull RK, Coulden R. CT measurement of main pulmonary artery diameter. Br J Radiol 1998; 71:1018-1020.

- Karazincir S, Balci A, Seyfeli E, Akoğlu S, Babayiğit C, Akgül F, Yalçin F, Eğilmez E. CT assessment of main pulmonary artery diameter. Diagn Interv Radiol 2008; 14:72-74.

- Kreutzer J, Landzberg MJ, Preminger TJ, Mandell VS, Treves ST, Reid LM, Lock JE. Isolated peripheral pulmonary artery stenoses in the adult. Circulation 1996; 93:1417-1423.

- Leuchte HH, Baumgartner RA, Nounou ME, Vogeser M, Neurohr C, Trautnitz M, Behr J. Brain natriuretic peptide is a prognostic parameter in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173:744-750.

- Hadengue A, Benhayoun MK, Lebrec D, Benhamou JP. Pulmonary hypertension complicating portal hypertension: prevalence and relation to splanchnic hemodynamics. Gastroenterol 1991; 100:520-528.

- Sen S, Biswas PK, Biswas J, Das TK, De BK. Primary pulmonary hypertension in cirrhosis of liver. Indian J Gastroenterol 1999; 18:158-160.

- Le Pavec J, Souza R, Herve P, Lebrec D, Savale L, Tcherakian C, Jaïs X, Yaïci A, Humbert M, Simonneau G, Sitbon O. Portopulmonary hypertension: survival and prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008; 178:637-643.

- Yang YY, Lin HC, Lee WC, Hou MC, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Portopulmonary hypertension: distinctive hemodynamic and clinical manifestations. J Gastroenterol 2001; 36:181-186.

- Chaouat A, Bugnet A, Kadaoui N, Schott R, Enache I, Ducolone A, Ehrhart M, Kessler R, Weitzenblum E. Severe pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172:189-194.

- Krowka MJ, Frantz RP, McGoon MD, Severson C, Plevak DJ, Wiesner RH. Improvement in pulmonary hemodynamics during intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin): A study of 15 patients with moderate to severe portopulmonary hypertension. Hepatology 1999; 30:641-648.

- Hoeper MM, Halank M, Marx C, Hoeffken G, Seyfarth HJ, Schauer J, Niedermeyer J, Winkler J. Bosentan therapy for portopulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2005; 25:502-508.

- Ota K, Shijo H, Kokawa H, Kubara K, Kim T, Akiyoshi N, Yokoyama M, Okumura M. Effects of nifedipine on hepatic venous pressure gradient and portal vein blood flow in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 10:198-204.