University of Washington

Seattle, WA

Program Director: Mark Tonelli, MD, MA

Type of Program: Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine

Abstract Authors: James A. Town, MD; Anna K. Brady, MD; Tyler J. Albert, MD; and Mark R. Tonelli, MD, MA MA

RATIONALE

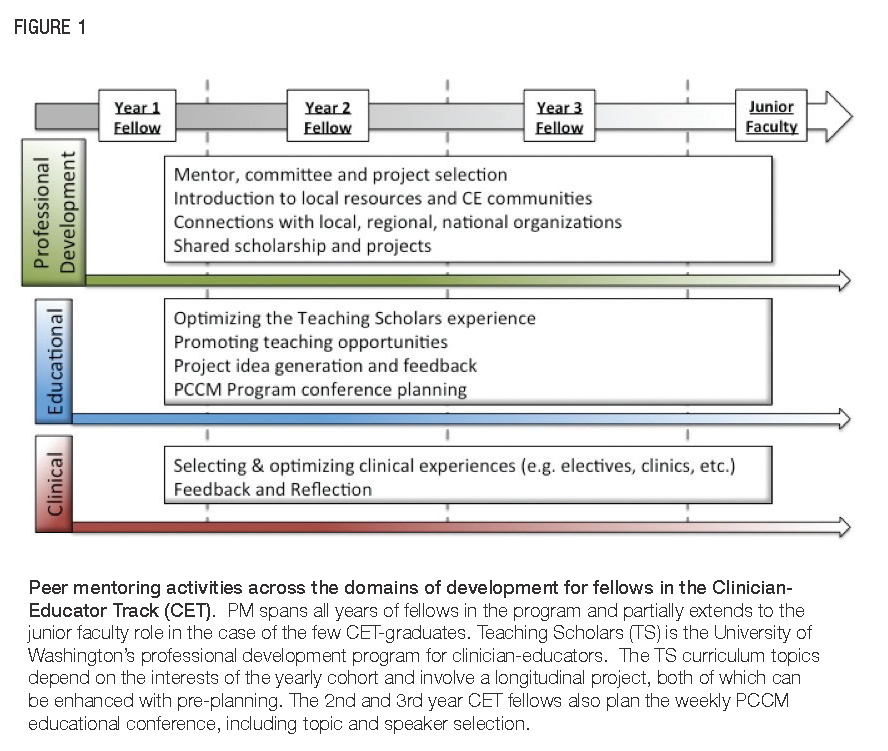

The original Clinician-Educator Track (CET) within our Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine (PCCM) Fellowship Program has been described (1); however, examining the evolving experience can optimize outcomes. Current CET fellows adopted peer mentoring (PM) to identify and enhance opportunities for fellows’ professional and educational development. Educational Strategy: CET fellows reflected on strategies to improve their training and selected PM to reduce barriers for timely, personalized, and pragmatic advising of each other. All PCCM fellows at UW have formal faculty mentors; however, the CET PM relationship mitigates hierarchy and offers perspective through a shared experience. PM offers a benefit at several levels to both peer mentors and mentees: mentees are advised on selection of faculty mentors, teaching opportunities, and other activities (see Figure 1). Likewise, peer mentors engage in professional development skills that are crucial to the clinician-educator. The PM relationship between CET fellows is informal and multidirectional, although senior fellows (and recent CET graduates) provide longitudinal context and experience.

PEER MENTORING IN THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The framework (Figure 1) depicts some of the PM activities of CET fellows progressing along the domains of clinician-educators: Clinical, Educational and Professional Development (2). PM itself is a component of both professional and educational development and gives fellows a stake in the pathway’s success. Challenges and Solutions: Compared to traditional physician-scientist pathways, no model exists for CETs and traditional mentoring may be less available for clinician-educators (3). Reflection and leadership by current and former CET fellows can advance the program’s outcomes. Adding the role of PM to the framework for CETs can help nascent CET programs identify mechanisms of support and growth to optimize fellow development.

EXPECTED IMPACT AND OUTCOMES

We report this active PM relationship as a powerful feature of the CET that can promote positive outcomes, build on successes, and serve as a model for other programs. Identifiable outcomes associated with PM include fellow co-authorship of peer-reviewed scholarship with recent CET graduates, strategies to maximize success in professional development programs, identification and recommendation of teaching opportunities, and shepherding junior fellows into roles within national organizations. In the future, peer mentors could be evaluated and provided with feedback with an internal tool currently used for faculty mentors and program-level data on academic progress (e.g., publications, committees, evaluations) could be assessed for correlation with mentoring relationships.

CONCLUSIONS

New CET programs should encourage PM as a useful developmental activity for their fellows.

REFERENCES

- Adamson R, Goodman RB, Kritek P, Luks AM, Tonelli MR, Benditt J. Training the teachers. The clinician-educator track of the university of washington pulmonary and critical care medicine fellowship program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(4):480-485.

- Roberts DH, Schwartzstein RM, Weinberger SE. Career development for the clinician-educator. Optimizing impact and maximizing success. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(2):254-259.

- Lord JA, Mourtzanos E, McLaren K, Murray SB, Kimmel RJ, Cowley DS. A peer mentoring group for junior clinician educators: four years’ experience. Acad Med. 2012;87(3):378-383.